Students working in our CORE Literature and Writing Discovery Guides will, each week, respond to “comprehension” questions that chronologically review the plot points from the week’s reading. But here, “comprehension” is an exercise that both draws students deeper into the heart of the story and the art of writing. Comprehension is a comprehensive exercise!

Comprehension is the act of making meaning from something heard or read.

Comprehensive includes all or nearly all elements or aspects of something.

There are many skills embedded into this complex activity beyond demonstrating that a passage has been well read. The act of responding to questions with a complete, detailed statement, is an opportunity for students to slow into the story details, but perhaps more importantly, to press into the work of constructing sentences.

*****

Following are two examples of the vast comprehensive nature of this weekly comprehension activity.

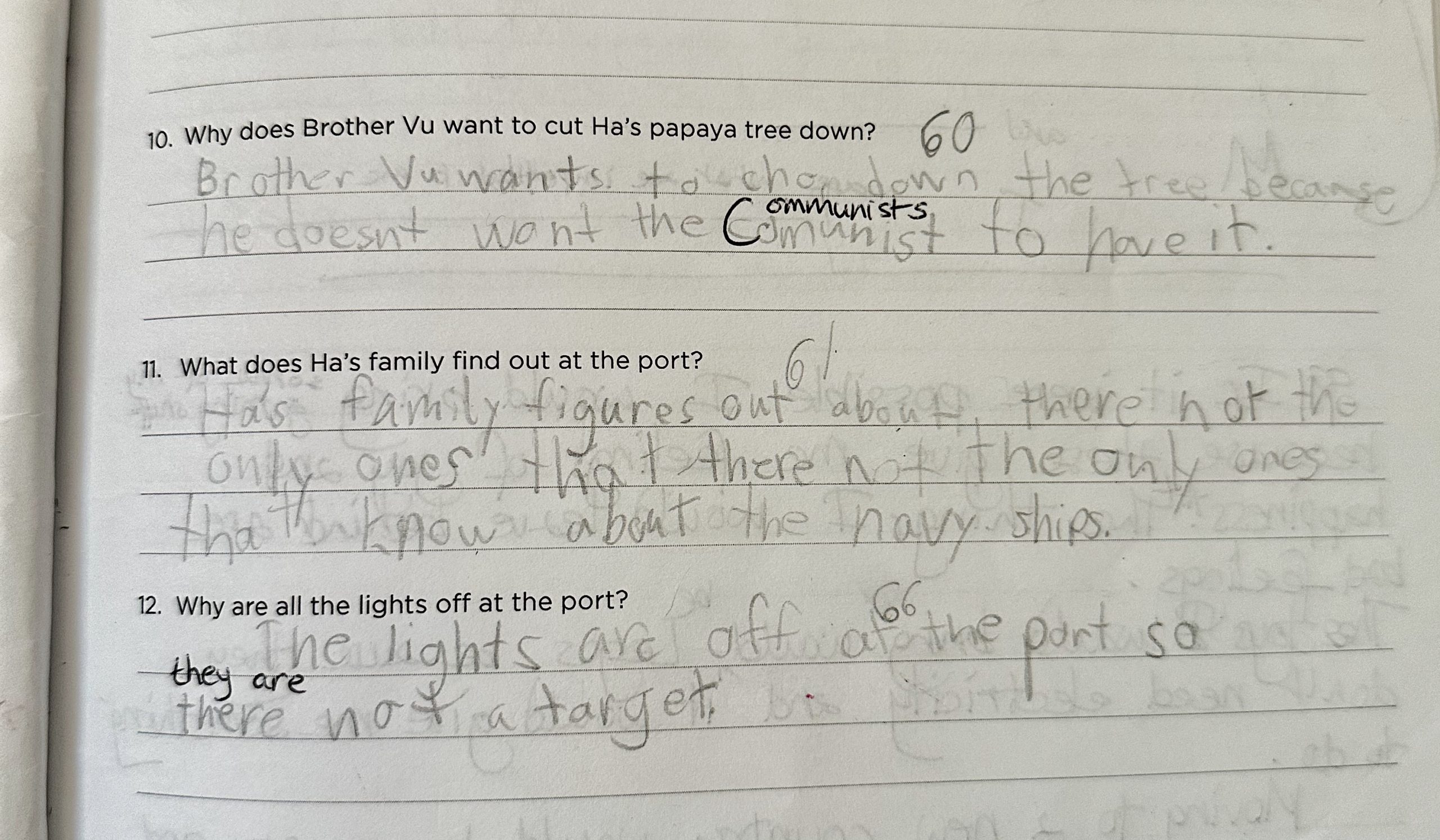

As a teacher, I scan the following sample from a student new to CORE Level 2, and notice common spelling errors—their, there, they’re as example. Capitalization too—Communists, Navy. But what I notice first is that each response is a complete, simple sentence construction that parallels the question asked. And this confirms to me this is not the place to be heavy handed with the red pen. Refer to the Teacher Helps for more information on complete sentence responses. I might however, write a little note in the comment space on the Assignment Checklist at the front of the student guide for this section:

Here’s a trick I use to remember the difference between this set of homonyms. Here the correct spelling is used in a correct setting: “their dog” AND “go there” (remember the’re is a contraction: they are)”they’re friends” … create your own trick and memorize the spelling of these!

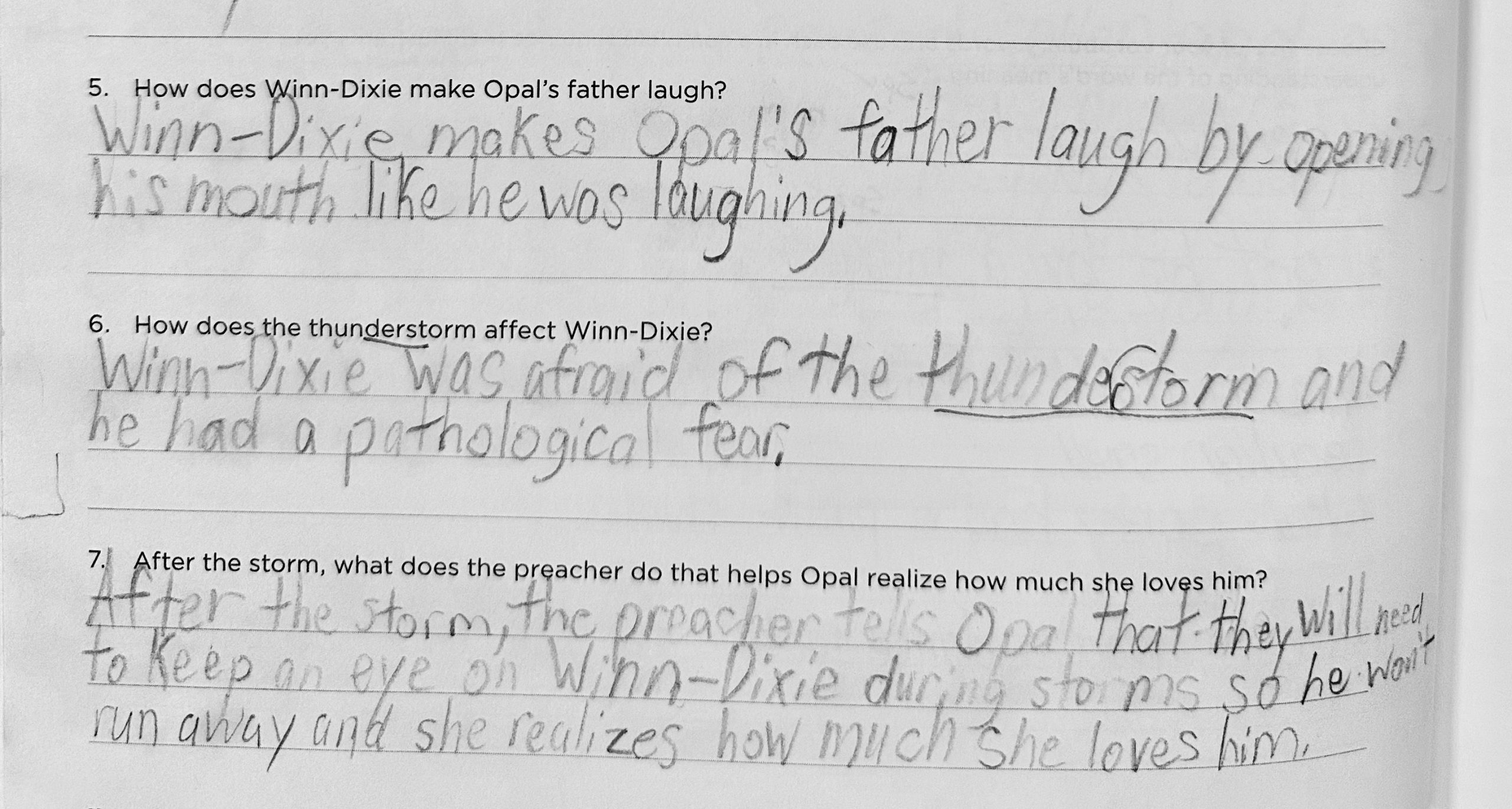

When a question is asked, students are free to respond independently:

How does Winn-Dixie make Opal’s Father laugh?

At first, sentence responses might be simple in nature copying the syntax of the question:

Winn Dixie makes Opal’s father laugh because he opens his mouth in a funny way.

[Here the teacher might suggest ways to smooth rhythm and add descriptive details: “Winn Dixie makes Opal’s father laugh when he opens his mouth in a funny way like he’s laughing.”]

Later, as students become more confident, sentences become more fluid, adopting more sophisticated syntax as in this dependent and independent clause:

When Winn Dixie opens his mouth to copy Opal’s father, he laughs.

[Here the teacher might suggest word choice: “Where you use the word “copy” you might try “mimic” instead.”]

The teacher does not need to correct every single sentence stylistically, but rather look for opportunities over time to inspire the writer to try new things. The best writing teacher will look for small opportunities over time to help students elevate their ideas. One or two suggestions modeled to the student over time is more effective than completing years and years of skill worksheets because this activity is the meaningful of work polishing students ideas.

Each year students using CORE Level 1, Level 2, and Level 3 Literature and Writing Discovery Guides will compose over 250 true sentences as they comprehend stories in comprehensive ways. Ultimately the work—the confident, beautiful, fluid work—will speak for itself!

~Kimberly