January 2024 is right around the corner!

Pages classes are designed to foster competence, creativity, and confidence in students as they press into the important work of becoming literate. Being able to communicate an original, BIG idea is the ultimate goal of English Language Arts.

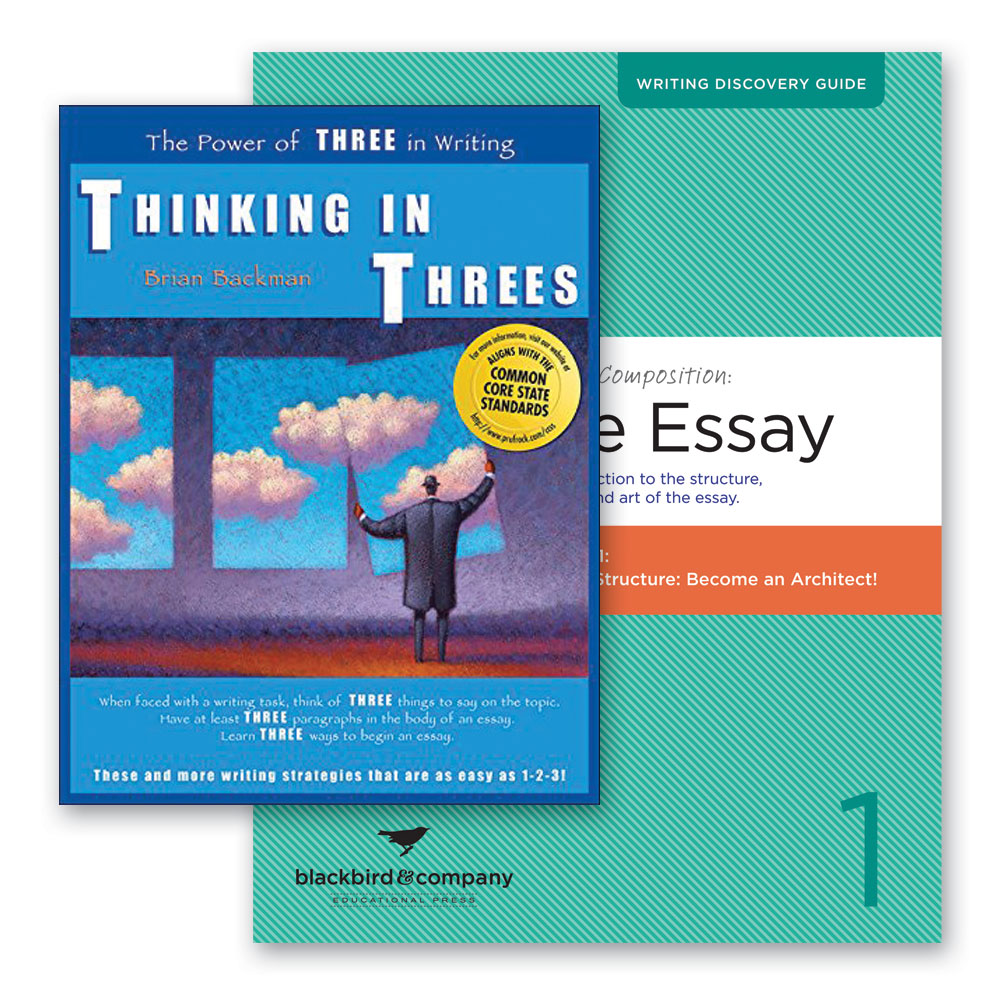

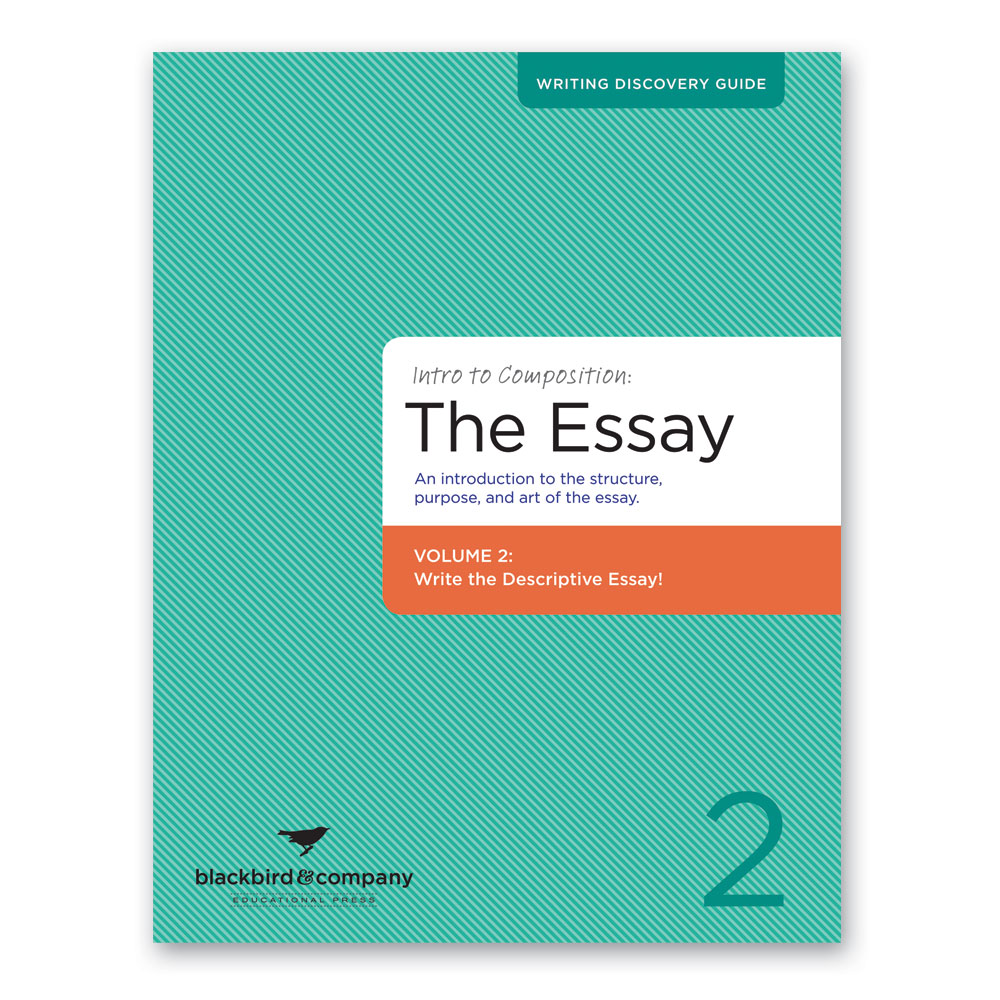

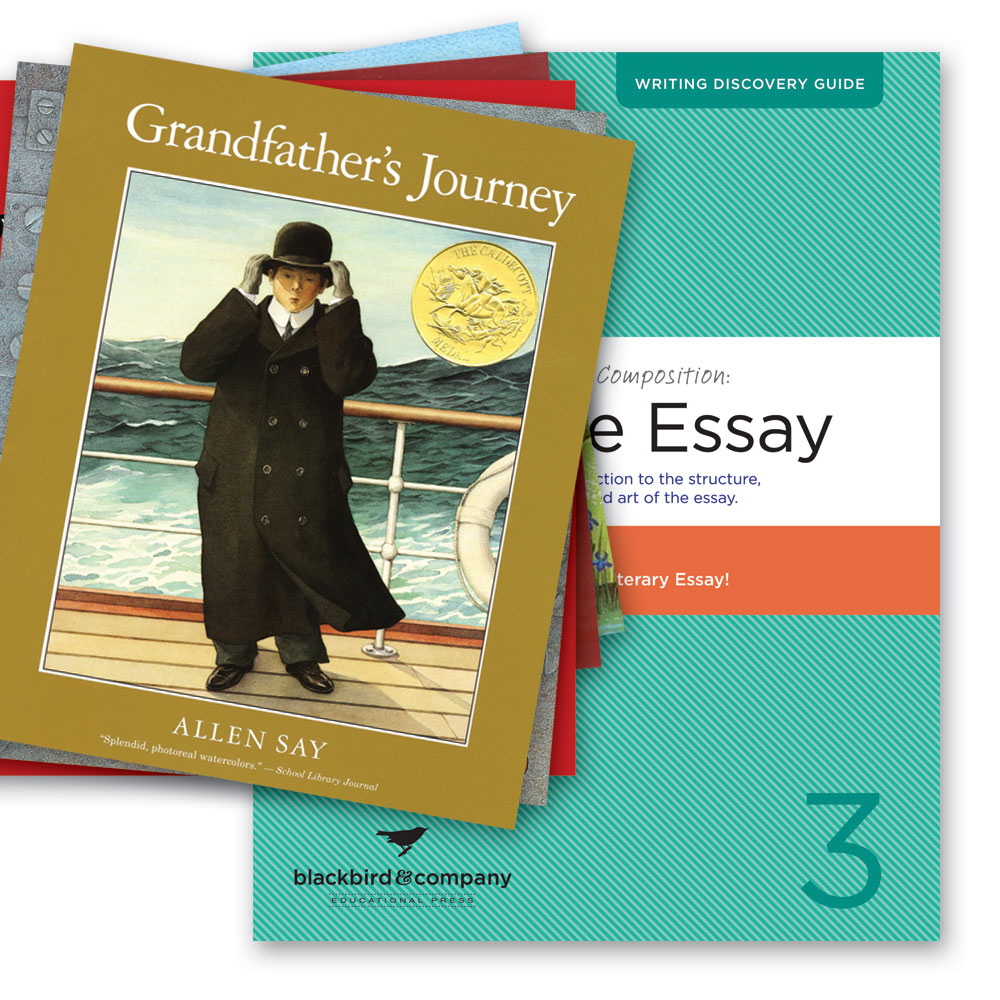

Get the most out of Blackbird & Company’s materials and methods! Classes range from 1-5 weekly sessions, and will kickstart your work with skills, tips, and tricks to help you succeed. We offer a wide range of humanities classes, all designed to explore the art of idea making:

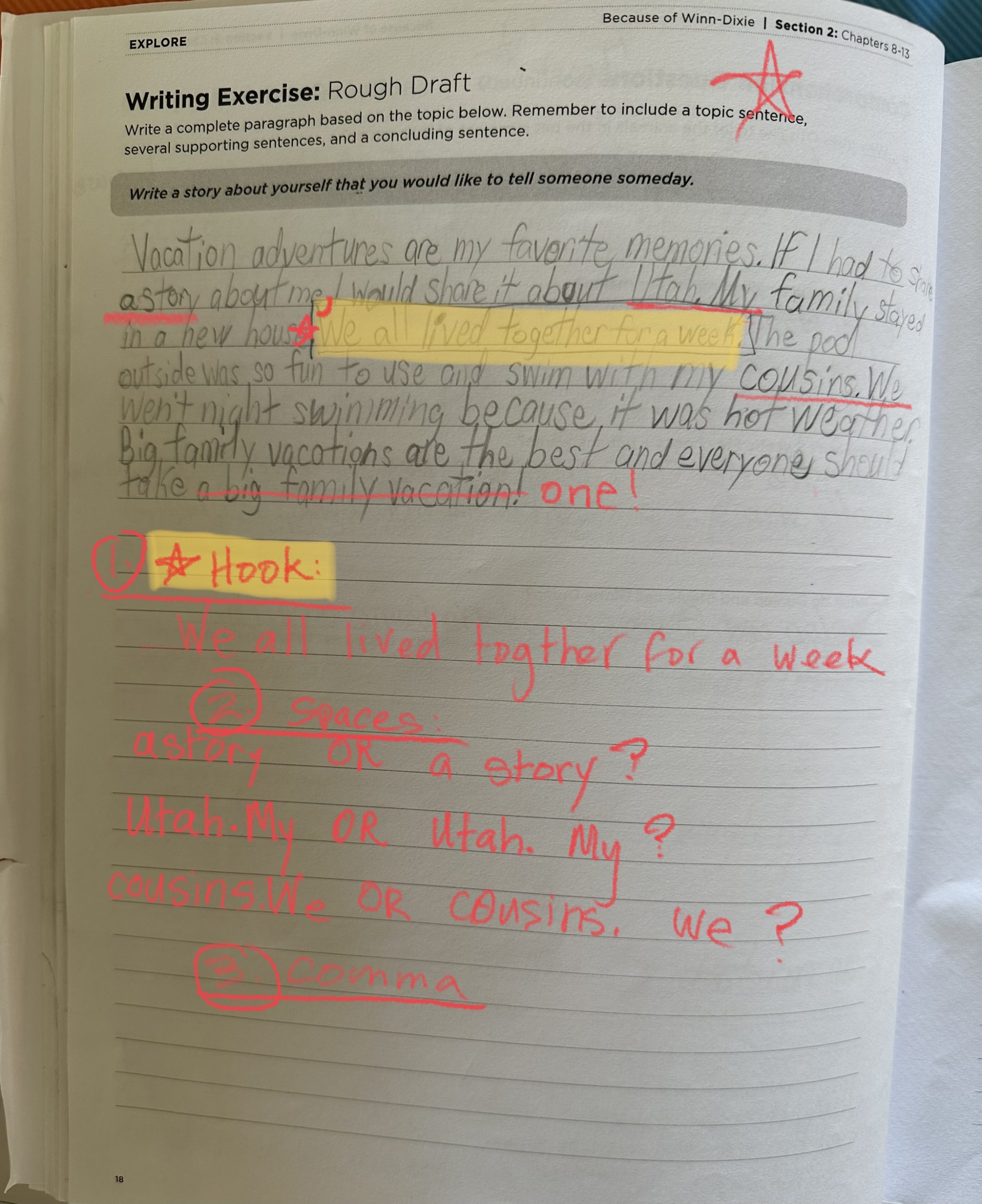

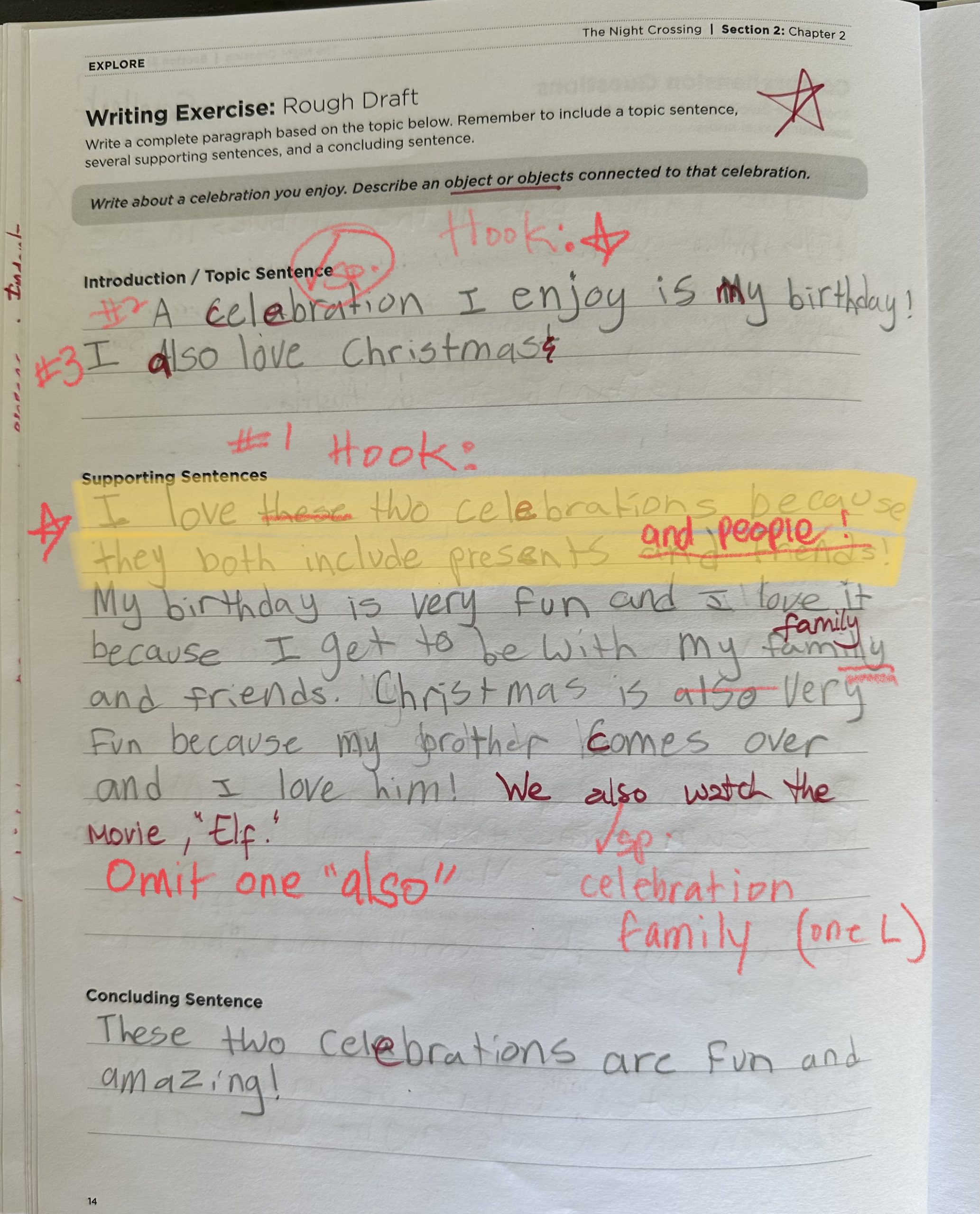

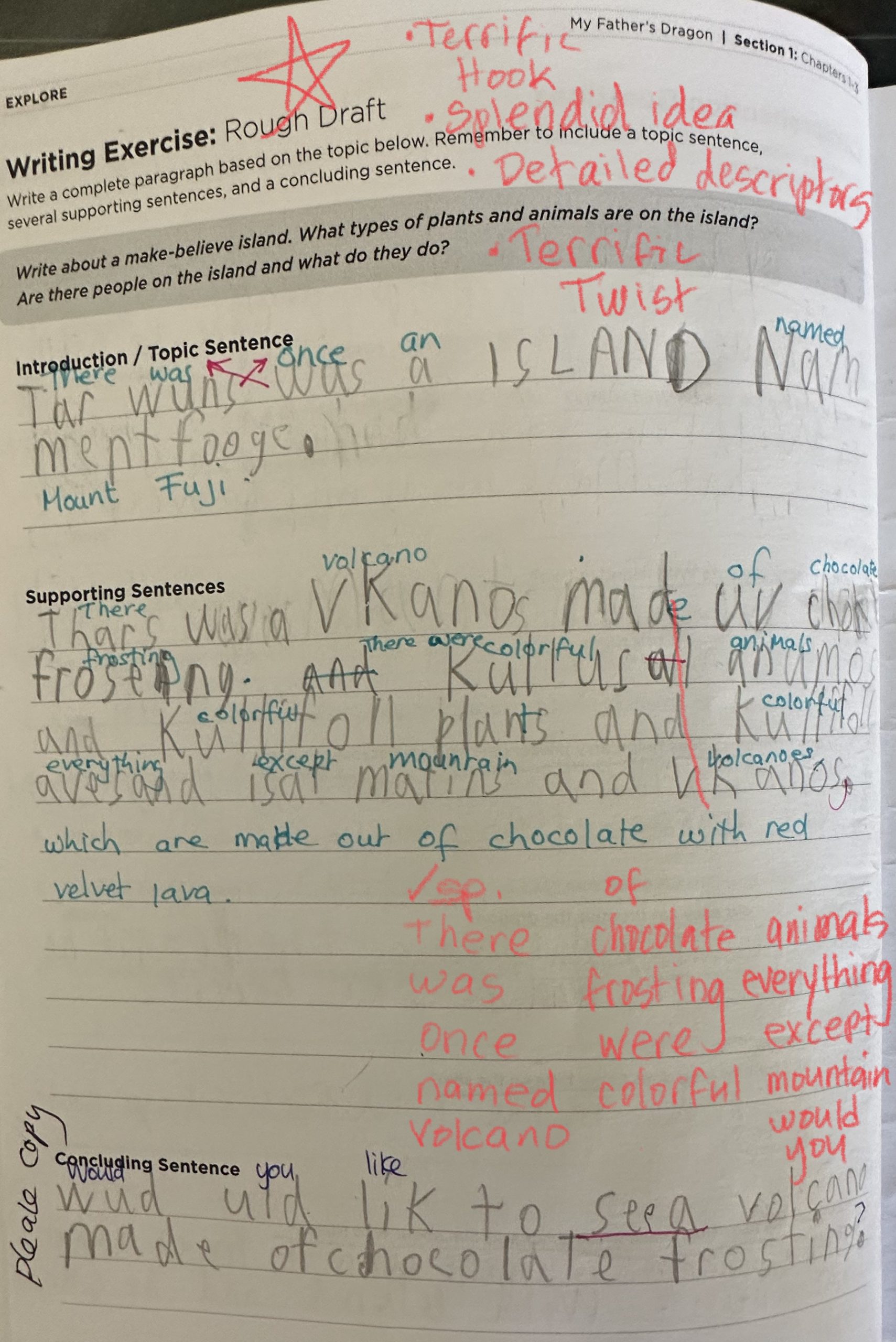

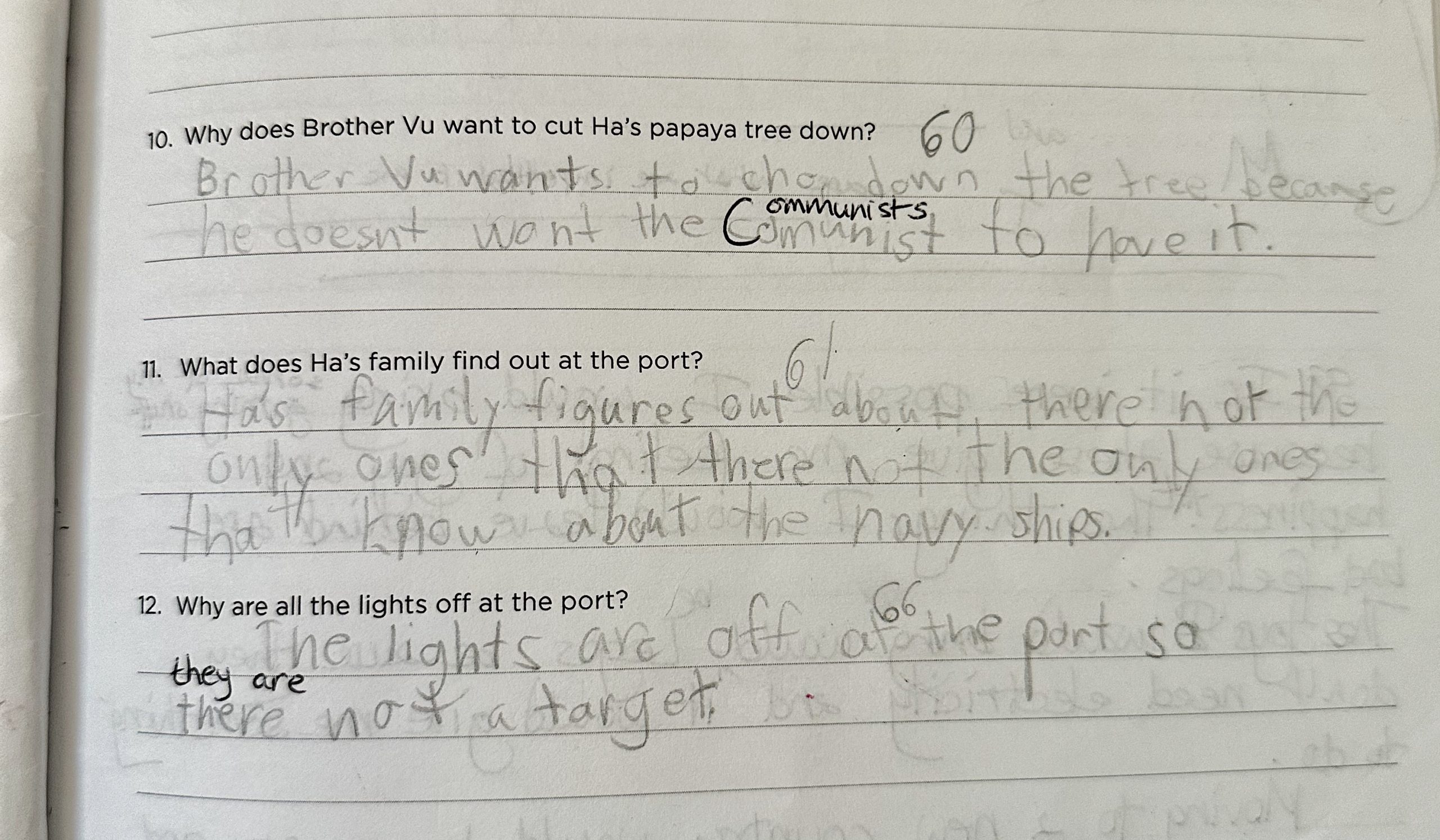

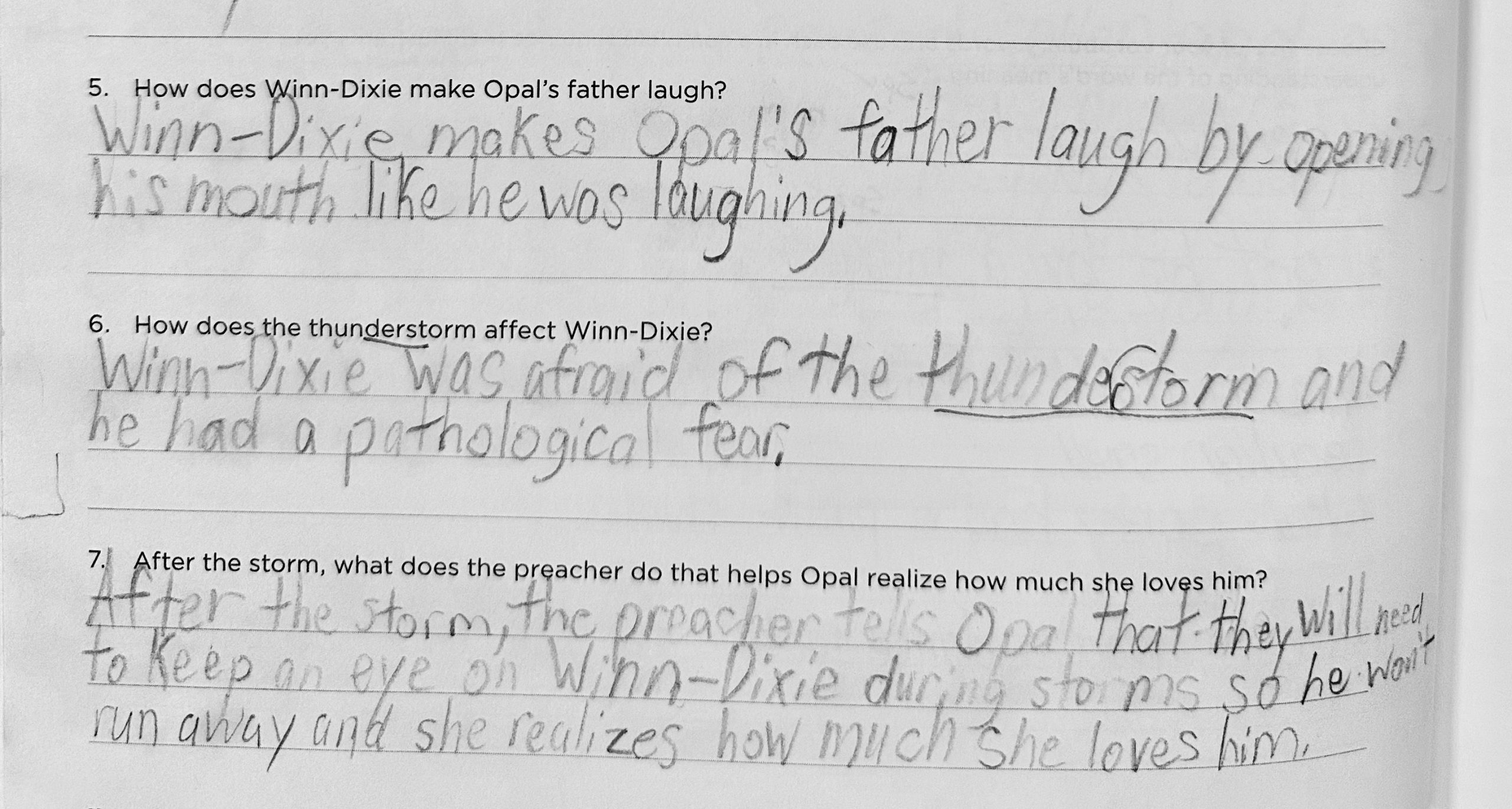

- CORE – Read and Write and Discuss! These classes are tied to individual Literature + Writing Discovery units (2nd grade through 12th grade). Students will receive weekly feedback on their writing via the one-on-one conference!

- The History Opt-in – These classes will provide extra historical background tied to specific CORE Level 2 (4th & 5th Grade), Level 3 (middle school), and Level 4 (high school) units. Students must be enrolled in CORE to participate.

- Research – Learn to explore the life of a famous person, extract fact, and write a unique biographical essay. Students are supported each step of the way.

- Creative Writing – Each session we are offering short thematic classes that will apply writing skills in beautifully creative ways.

- Visual Arts – Explore great works of art and their makers. Students will learn about and practice art making while gaining skills that will transfer to all areas of academic pursuit, especially the art of writing.

- Music – Explore the works of great composers and the language of music. Students will gain skills that will transfer to all areas of academic pursuit, especially the art of writing.

Enroll today!

What parents are saying about Pages:

“Thank you for making class so enjoyable and personal. My daughter’s writing has really expanded since being in classes with you.” ~Brit Riddle

“I really appreciate you going through the different areas of reading and writing in class as opposed to having him do it all on his own at home. It sets a good example of what to do (i.e. what to look for and pay close attention to as he reads) and how to do it (i.e. organize his thoughts and get ready to write into paragraphs).” ~Paulina Yeung

~Kimberly