When we teach a student calculus, we are teaching them to attend to small parts of a larger form. The word calculus comes from the Latin, meaning small pebble.

When we teach a student calculus, we are teaching them to attend to small parts of a larger form. The word calculus comes from the Latin, meaning small pebble.

When teaching our students to write, we should begin by teaching them writing is an art form!

So why have we turned the art of writing into a calculus?

Great writing never begins with capitalization, punctuation, or grammar!

Great writing begins with an IDEA!

Writers must focus first on the function or purpose of writing—the idea. Once the idea is drafted in rough form, the writer digs back in and applies mechanics—corrects misspelling, capitalization, punctuation, embellishes word choice, improves syntax, and so on. Writing is a process.

So, let me clarify, I’m NOT saying don’t teach capitalization, punctuation, or grammar. I’m simply saying that primarily focusing on mechanics over and above actually constructing ideas will never produce exceptional writing.

The best way to learn to write is to WRITE.

Who, when asked to write a sentence about an apple, will begin like this: “I will need an interesting adjective, an adverbial phrase, plus a dependent and independent clause,” with a deep dive into grammar and mechanics and rhetoric? NO! You will pick up your pencil and you will write your idea! Once you get an idea on paper, you will, as time permits, reread and polish that idea—improving word choice here and there, possibly rearranging phrases, correcting spelling and capitalization and so on. Writing, like all art forms, requires that the writer engage in a process.

For the past 30 years, in addition to educating my own children (who are now thriving adult readers and writers), I’ve guided countless students through our CORE Literature and Writing Discovery Guides. And what I’ve learned is this:

The key to success over time?

Choose your battles.

Each week in the CORE Literature and Writing Discovery Guides, students will encounter a writing prompt inspired by the week’s reading. These prompts will require different types of responses utilizing different types or domains of writing—narrative, observational, imaginary, persuasive, and so on.

The weekly writing prompt will:

1) Allow students to write their ideas in a vast array of writing domains.

2) Move students through the process of constructing ideas, from draft to polished form.

3) Motivate students to engage in the work of idea making.

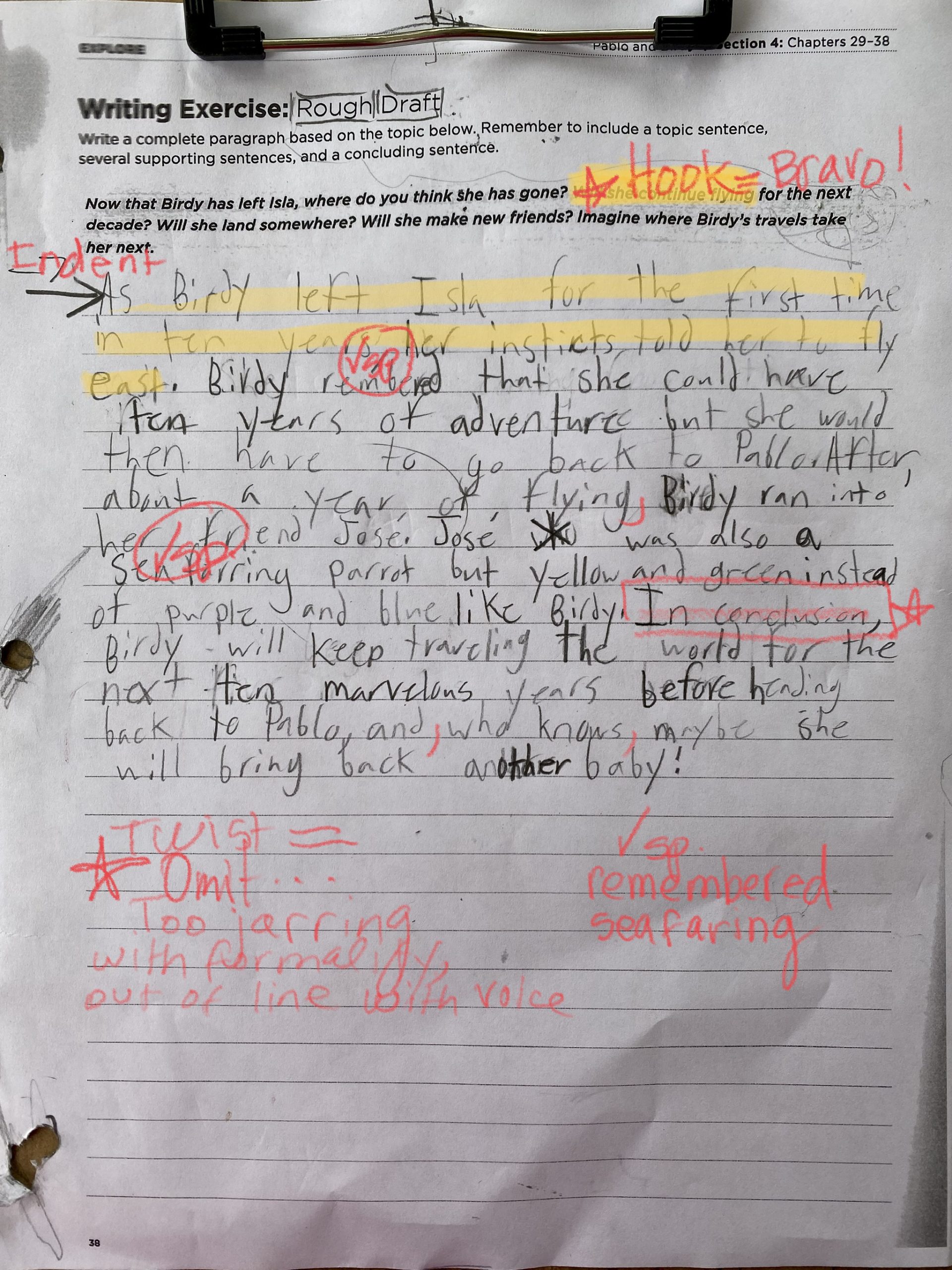

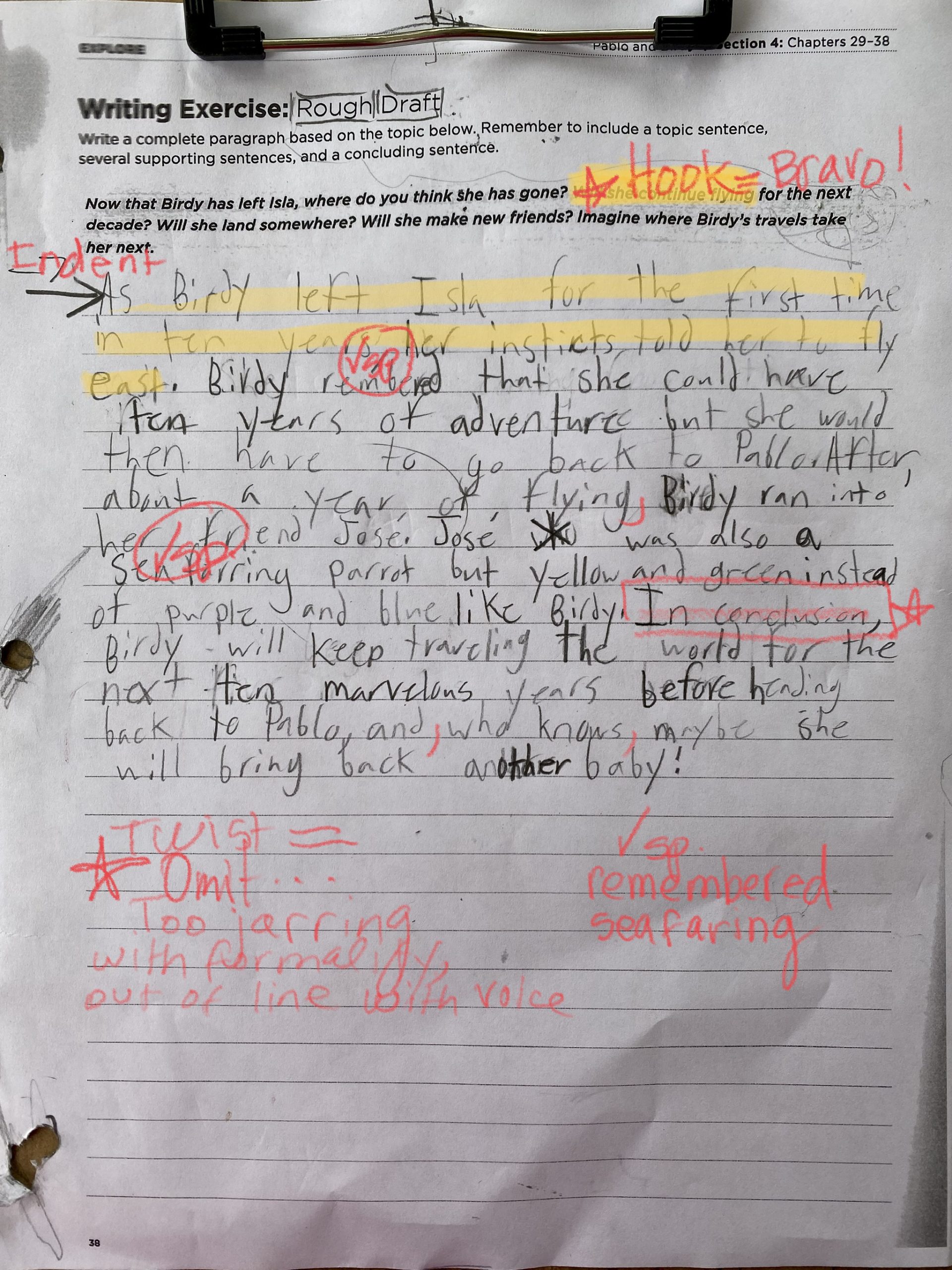

The best writing teacher is a mentor who encourages the student’s idea. This 4th grade student is responding to the Section 4 prompt in the Pablo and Birdy student guide. You can see by simply reading, that this young writer cares about the idea being constructed. You can see by examining the effort made to communicate the idea coherently. Like any construction zone, this is messy, there are sections scratched out, there is scribble in the margin, there is darkened in pencil where spelling is being considered by the student writer. This is all GOOD!

How to Conference One-on-One:

During the 5-minute conference (keep it pithy), have the student read aloud what is written on the page. Use your red pen to make edits and suggestions as the work is being read aloud. For this paragraph, I focused on the following 4 topics:

The HOOK

This is something that is a focus each week, teaching students to open their idea with a sentence that moves beyond a “topic opener” toward a sentence that actually HOOKS the reader into the idea. This writer, who had been working in our CORE for over a year, opened this with a really well constructed, informative sentence—a terrific hook! What’s so great about this sentence? Consider that less experienced writers might write something like this:

Birdy left Isla to fly away.

This sentence is a very flat statement, lacking the detail that engages readers to read on. But this type of simple sentence is often where young writers begin. The goal of the teacher is never to re-write the hook, but rather to encourage the student to add details. Why did Birdy fly away? Where did Birdy fly? In the sentence written by this student, there is also a bit of intrigue in the phrase “for the first time in ten years” that makes the reader sense a bit of courage in the act of flying away!

As Birdy left Isla for the first time in ten years, her instincts told her to fly east.

Indentation

The indentation is a small, but constant reminder.

Spelling

I typically don’t make writers look up misspellings in a dictionary, but rather create a checklist in one of the white spaces on the rough draft. As the student reads I am checking misspelled words, then, as I discuss what I’ve discovered after the read, I make the corrected spelling list. There are two misspellings in this paragraph.

Twist at the End

The TWIST at the end has a bigger purpose than concluding. The last sentence of an idea should keep the idea in the reader’s mind to ruminate and ponder. With the phrase “in conclusion” at the beginning of this student’s Twist, the reader is jarred from the flow of the lovely narrative. Something about this phrase is out of sync with the rest of the voice. The phrase is formulaic. Simply omitting it transforms the last sentence:

(In conclusion,) Birdy will keep traveling the world for the next ten marvelous years before heading back to Pablo, and, who knows, maybe she will bring back another baby!

This statement is actually a rhetorical question, so the exclamation mark at the end is acceptable.

Imagine now this sentence with different syntax:

For the next ten marvelous years before heading back to Pablo, Birdy will keep traveling the world, and, who knows, maybe she will bring back another baby!

This rearranging was not offered because I felt the student’s sentence (minus “in conclusion”) was lovely as is. However, it’s always good to imagine possibility and to have many tricks up your sleeve!

Ultimately, if you can read, if you can enjoy an idea, and if you can be delighted in the potential of language, then roll up your sleeves and get into the garden!

~Kimberly

Let’s start a tradition!

Let’s start a tradition!

When we teach a student calculus, we are teaching them to attend to small parts of a larger form. The word calculus comes from the Latin, meaning small pebble.

When we teach a student calculus, we are teaching them to attend to small parts of a larger form. The word calculus comes from the Latin, meaning small pebble.