To read is to imagine.

To imagine is to story tell.

To story tell is to write.

This last weekend we went and saw my son in a performance of Mary Poppins. He had been rehearsing for months and it was finally his time to “wow” the audience from the big stage. Everyone came armed with their role and their costumes and their props and their accents. The stage was transformed and we were transported to London in 1910. The main stars of Mary Poppins are of course, Mary Poppins and her magical chimney-sweep friend, Bert. But the story itself really centers around the father, Mr. Banks, who sees his role as a father as strictly providing and not in nurturing. As the musical performance played out, the audience experienced the magic, the struggle and the transformation in the family and especially in the father. Mr. Banks was no longer a 14-year-old boy, but a man struggling in his role of provider, husband, and father.

I reflected later that we as human beings need to share our ideas, feelings, and stories. I never could know how it felt to live and be the head of a house hold in 1910, in London. Things we will never experience, we can feel and learn through stories.

In Pages online, we read a terrific story during this last session with my middle school Level 3 students called Banner in the Sky. This book was about a boy climbing the highest mountain, the Citadel, in the Swiss Alps. It is a fictional book but based on real research and experience climbing. As we read, we were transported to these mountains, holding on for our lives, experiencing the harsh weather conditions and the strength of the climbers both physically and mentally. Before this book I had never pondered what climbers experience.

Books take us places we have never been to experience things we will never do.

Through books we get a glimpse of the past we never experienced. We learn about things we have never done. We ponder what things might be like in the future. In my Level 4 Pages class, we read The Giver—a book that talks of a newly created community where everyone lives in sameness, under a set of rules where the weak and rule breakers are sent to Elsewhere. Memories are too painful for people, so they are taken away and placed with one single person, a person separate from society, called the Giver. The book is set in an unspecified future with no exact date. This young adult dystopian novel was written in 1993 and has sparked questions about conformity, individuality, unexamined security, freedom and the importance of our past and experiencing pain.

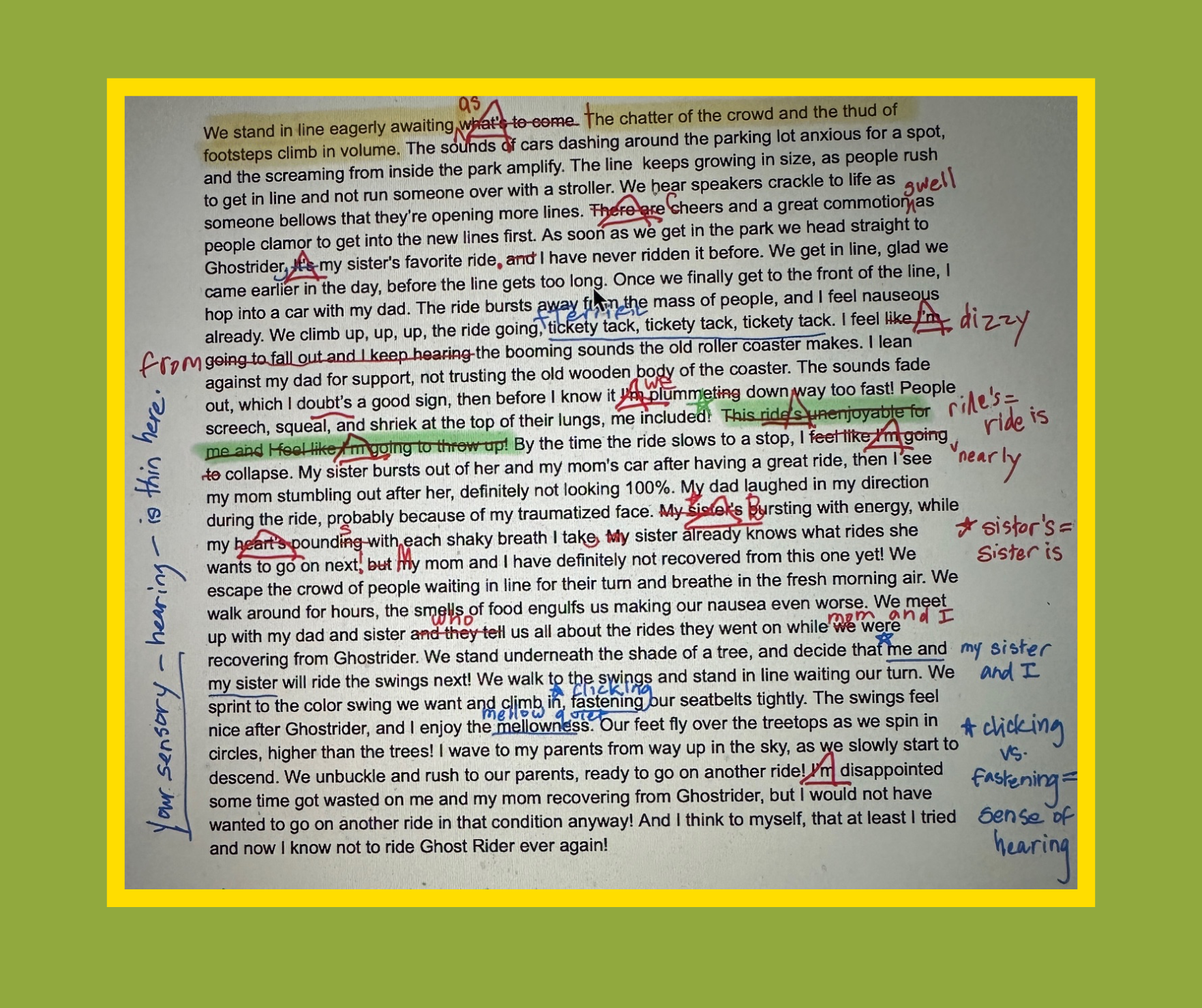

Blackbird and Company has created curriculum to accompany the journey and adventure of books; comprehension, setting, plot, vocabulary, themes, motifs and symbols are covered. But we really dive deep when we ask the student or should I say the writer to write, their ideas, feelings, opinions, beliefs. Our prompts ask, what tricky or fearful experience have you encountered? How did you get through? What would you do if faced in the same situation as the character? What do you want to do when you get older? Who influenced you?

Suddenly we are telling a story—our story—we are the writer of our story!

To write, we need only to start with a word, a phase, then one true sentence. It sounds so simple, but the words we choose to use are important, meaningful. We can paint pictures with our words, create dramatic scenes, show painful, tragic moments, create laughter, and love. In the performance of Mary Poppins, one of my favorite scenes is when they sing the song, Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious! Mary Poppins, inventor of this word, gets the whole stage singing her brand new magical word! Simply said, it is something to say, when you have nothing to say!

When you look up “supercalifragilisticexpialidocious” (the magical word of Mary Poppins) in the dictionary, there it is, defined as: something extremely good or wonderful.

What a challenge that word would be to put in an essay, but much more powerful, might I say magical, than simply saying something is good.

Mary Poppins would say to our students: Learn words, words and more words!

By the age of 5 years old children recognize at least 10,000 words. By 10-years-old, children can speak and write an average of 20,000 words and learn on average 20 new words a day. They can also understand the fact that words have multiple meanings. A High school student may know anywhere from 25,000-50,000 words. When I looked up the average vocabulary for adults, it ranged from 20,000-35,000 words. Children double their vocabulary between 5 and 10-years-old, learning an average of 20 new words a day! But over 10-years-old, learning new vocabulary slows or even stops. An average teen or adult might just have a vocabulary of 25,000 words. That’s only 5,000 more than a 10-year-old, maybe staying this way for their lifetime.

We have moved away from books you hold in your hand and dictionaries you flip through. We’ve have moved to media. As a whole we have moved away from writing with a pencil and instead typing on the computer.

How do we inspire our students to read and to write and to thing? How do we keep them learning, and adding to their vocabulary? To become the communicators of the future? How do we inspire our students to be writers who express that wonderful one true sentence? To bring that idea, that feeling, that story to life? How do we make what feels impossible, possible?

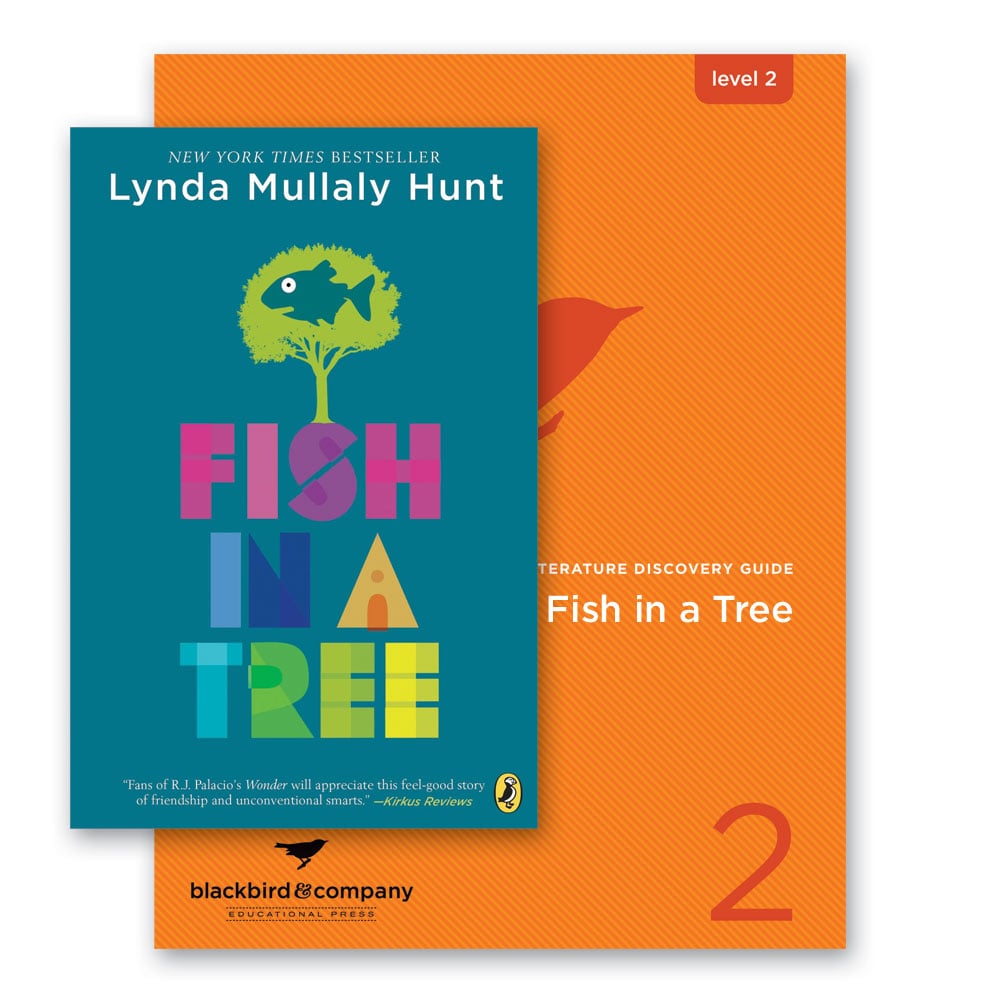

Mr. Daniels, of Fish in a Tree, instructs the main character, Ally, to draw a line between the M and the P in that word impossible.

I M / P O S S I B L E

“So, now, Ally…….that big piece of paper in your hand says possible. There is no impossible anymore, okay?”

We can create possibility. We can create words and meaning. The possible starts with YOU. And the way I see it, with a good book and some time.

“In this world of words, sometimes they just can’t say everything.”

Or can they? I would like to find out!

~Clare

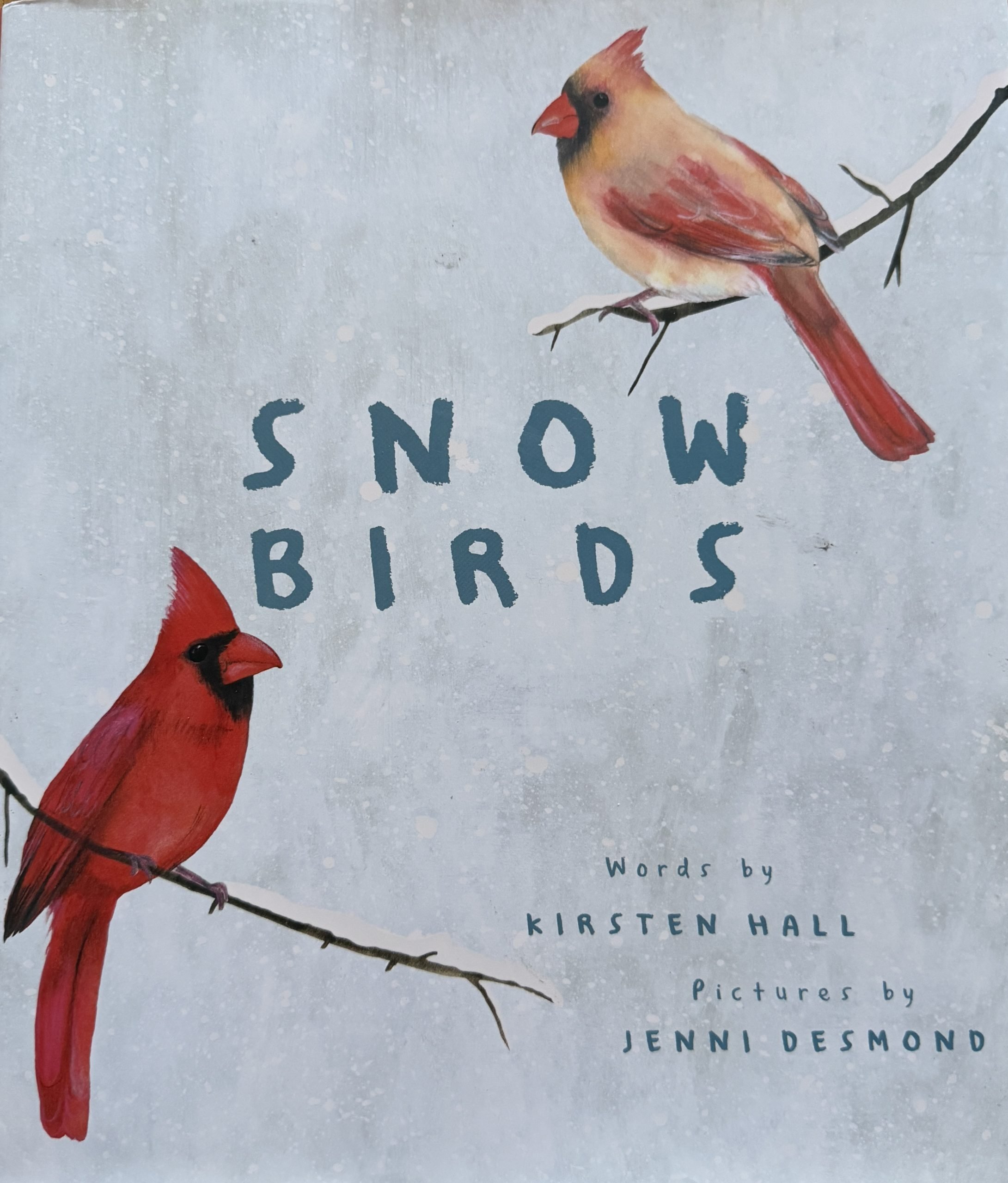

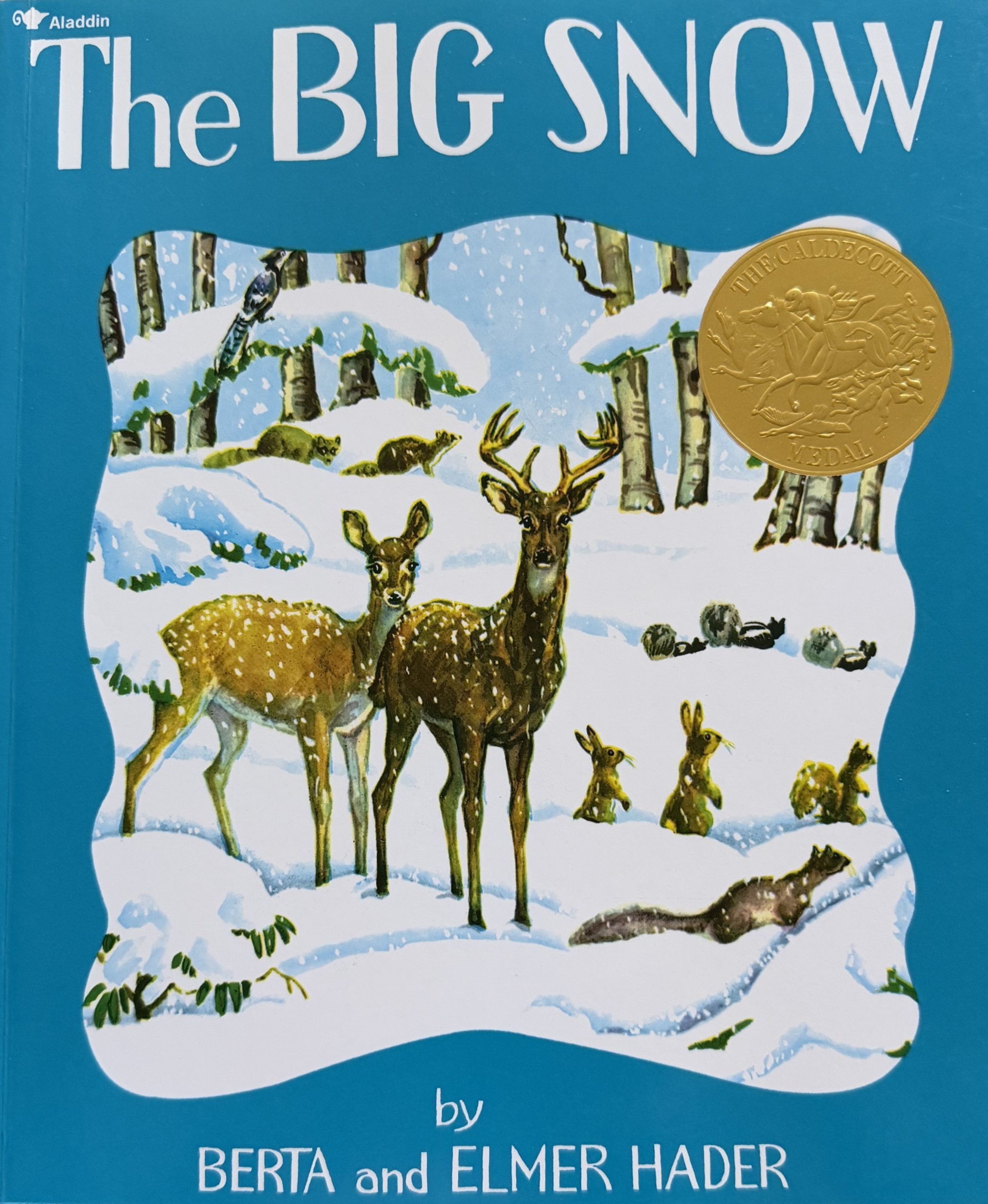

The woodland animals were all getting ready for the winter. Geese flew south, rabbits and deer grew thick warm coats, and the raccoons and chipmunks lay down for a long winter nap. Come Christmastime, the wise owls were the first to see the rainbow around the moon. It was a sure sign that the big snow was on its way.

The woodland animals were all getting ready for the winter. Geese flew south, rabbits and deer grew thick warm coats, and the raccoons and chipmunks lay down for a long winter nap. Come Christmastime, the wise owls were the first to see the rainbow around the moon. It was a sure sign that the big snow was on its way.