Squirrels are everywhere. That’s for sure! Most young writers have had a squirrel encounter or two. Tapping into a rich storehouse of knowledge is a great place to learn to craft a HOOK—not a topic sentence, a HOOK! The best place to begin a writing lesson is to tap into what the writer knows and to read a book.

Nuts to You by Lois Ehlert is a gorgeous and simple story of a quintessential city squirrel who, naturally, zips mischievously through life. Told in lively rhyming verse with beautiful collage illustration, the book is sure to capture the attention of students. At the back of the book the author includes some terrific facts about squirrels. We chose five facts to focus on:

Five Facts About Squirrels

1. Squirrels are rodents

2. They have front teeth—incisors—that NEVER stop growing.

3. They live in big nests or hollow trees.

4. They have five toes on their front feet, four on their back.

5. Their bushy tail is as long as its body.

Often times, when facing the blank page, students are intimidated and resort to simplistic, and, well, let’s face it, BORING solutions! Young writers resort to what they have been taught: Open your paragraph with a topic sentence. This is not technically wrong. But we can BETTER equip them!

For example these perfectly fine topic sentence are boring:

Squirrels are cute animals.

Squirrels are everywhere.

And my least favorite topic sentence of all:

I am going to write about squirrels.

So how do we teach our students to make topic sentences sparkle and shine?

We teach the to transform the topic sentence into a HOOK!

To help them get there, I gave them a BIGGER squirrel fact: Did you know that squirrels are everywhere in the world except Madagascar and Australia? We looked at a globe together and marveled at this interesting fact!

Next, I asked them what kinds of noises squirrels make. I got some very fun responses, too! I told them that we writers like to create words that represent sounds and, when we do it’s called: onomatopoeia. They liked that word! Now it was time to craft a HOOK for our paragraph about squirrels.

“Let’s imagine what it would sound like if we could hear all the squirrels all over the world.”

We generated a significant list:

Barking, Chirping Squeaking Squawking, Whistling Scampering Scratching Gnawing Grinding, Rattling, Buzzing, Crying

Next I said, “Let’s include our BIG fact via an Em Dash,” and went on to remind them that this special punctuation mark helps the reader take a long pause while adding some important information to the sentence.

Now we had our fodder and were ready to craft a HOOK! Here’s were we landed:

They are chattering, chirping, squawking all over the wide world—everywhere except Madagascar and Australia.

That’s the way to open a paragraph about squirrels!

~Kimberly

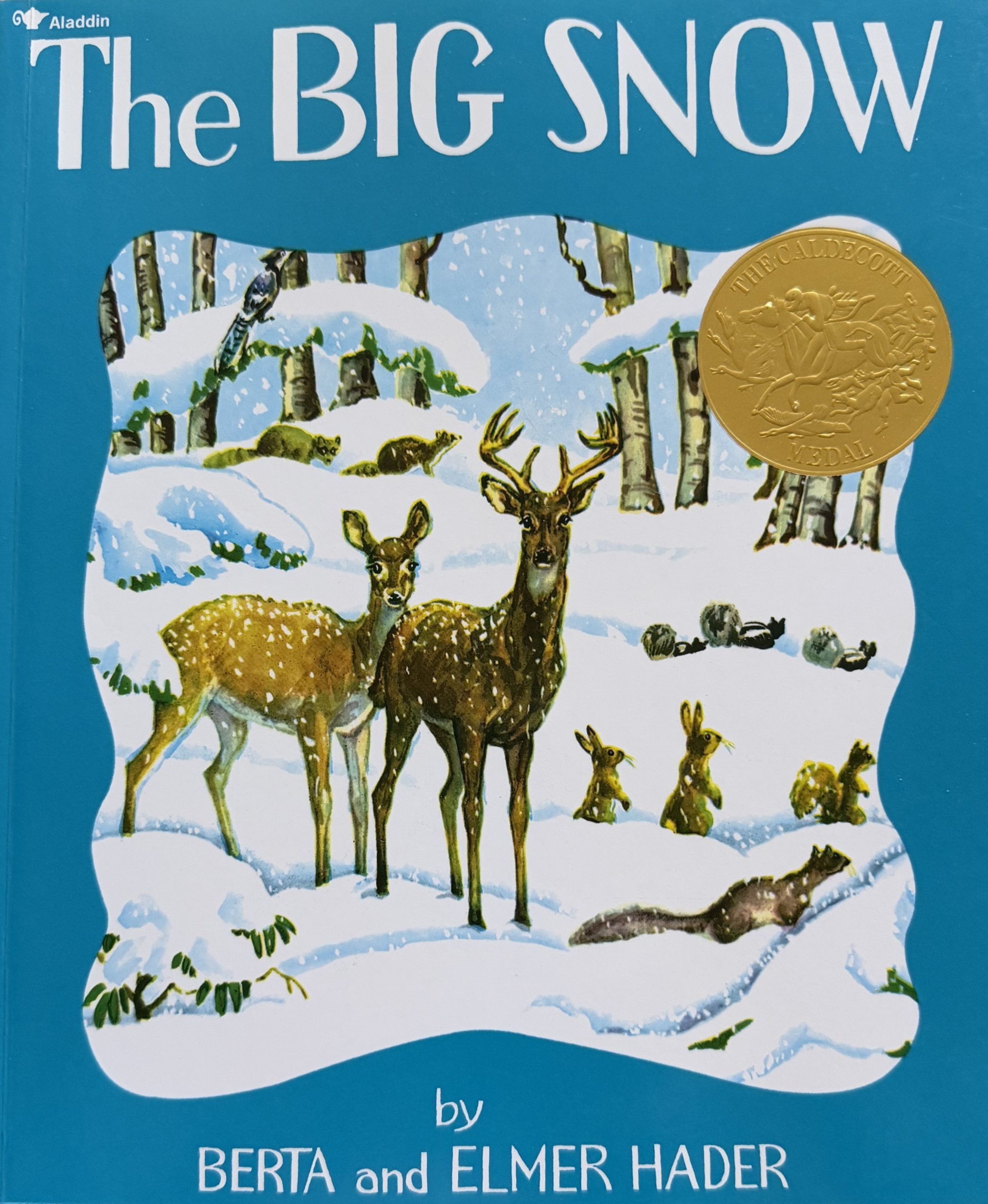

The woodland animals were all getting ready for the winter. Geese flew south, rabbits and deer grew thick warm coats, and the raccoons and chipmunks lay down for a long winter nap. Come Christmastime, the wise owls were the first to see the rainbow around the moon. It was a sure sign that the big snow was on its way.

The woodland animals were all getting ready for the winter. Geese flew south, rabbits and deer grew thick warm coats, and the raccoons and chipmunks lay down for a long winter nap. Come Christmastime, the wise owls were the first to see the rainbow around the moon. It was a sure sign that the big snow was on its way.