Never be afraid to ask questions!

You can teach your children.

You can teach them well!

We’ve developed tools to help you and your students succeed. However, when it comes to early English Language Arts, the vast array of terms that describe the scope and sequence children must assimilate on the path toward literacy is daunting. There are 44 phonemes (sounds) in the English language, but there are around 250 graphemes (letters or combinations of letters that represent single sounds)!

Tip 5

Ask questions!

As mentioned in my last post, having a mentor and a tribe of support was a wonderful part of my homeschool journey. These are people who encouraged and cheered me on! These are the people I peppered with questions along the way!

We hope that you will consider us part of your tribe.

Anticipating your questions, we’ve developed a thin little Teacher Helps to accompany both Hatchling, Volume 1 for kindergarten and Volume 2 for 1st grade. Inside this volume you read all about the world of early ELA—phonics, sight words, journalling, spelling, and the scope and sequence of literacy! When it comes to questions, we encourage you to read through your Teacher Helps and to take a really thorough sneak peak into the student journals. Hopefully this material will answer many of the questions that you have about beginning and sustaining learning. But you will have more, I certainly did! Read again, underline, write notes in the margins.

Below are four questions as example of the many answers embedded in our Teacher Helps for Hatchling.

ONE.

Why study phonics?

On page 9 in our Teacher Helps, we explain why phonics. Phonics is a method of teaching students to read and write (notice we mention these together, at the same time). Phonics is a method of teaching students to read and write by helping them hear, identify and manipulate phonemes. We start at the beginning the A, B, C’s when learning to read and write. Letters represent the sounds we speak and hear -this is phonemes! Phonics is an organized, logical system but the English language has 26 letters of the alphabet when combined in various ways create the 44 sounds or phonemes. In Latin/Greek phone means “voice or sound”. The written letters are called Grapheme’s. In Latin/Greek graph means “to write or written”. When referring to the name of a letter we put the letter in quotes, “a”. When referring to a sound a letter makes we put the sound between two slopping lines, /a/. With so many letters and combination of letters it is best to teach sounds over names. This takes time, practice, play, visual and hands on materials.

TWO.

Why spell through phonics?

On page 12 in our Teacher Helps we explain why spell through phonics. During the primary years (1-3 grades) students will spend a lot of time and effort understanding how to encode print words using the English alphabet. Encoding is essentially a writing process. Encoding breaks a spoken word down into parts that are written or spelled out. Decoding on the other hand breaks a written word into parts that are verbally spoken. Our approach moves the student from the concrete, familiar objects to teach phonemes easing them into the complicated abstract world of spelling. Students get insight into the world of language, wowed that sounds make words, words combine to make phrases, phrases combine to make sentences and sentences combine to make passages.

THREE.

How do I know if my student has mastered a skill?

How to review, practice, and check for understanding while learning these specific phonemes is listed on page 10 in the Teacher Helps. How to review High Frequency Sight Words is on page 13. We talk bout why handwriting is an essential skill on page 14, when it comes to early literacy. The art of handwriting promotes focus, fluency and flourish. The work of writing something down allows students to focus on form itself, enlisting executive function and promoting purposed attention. This focus transfers to all other learning. The work of writing something down strengthens fluency, fluency allows students to express ideas. Being imaginative and curious begins in our minds. Writing something down helps the student to flourish by elevating ideas and reinforcing the work of idea making.

FOUR.

What about pencil work?

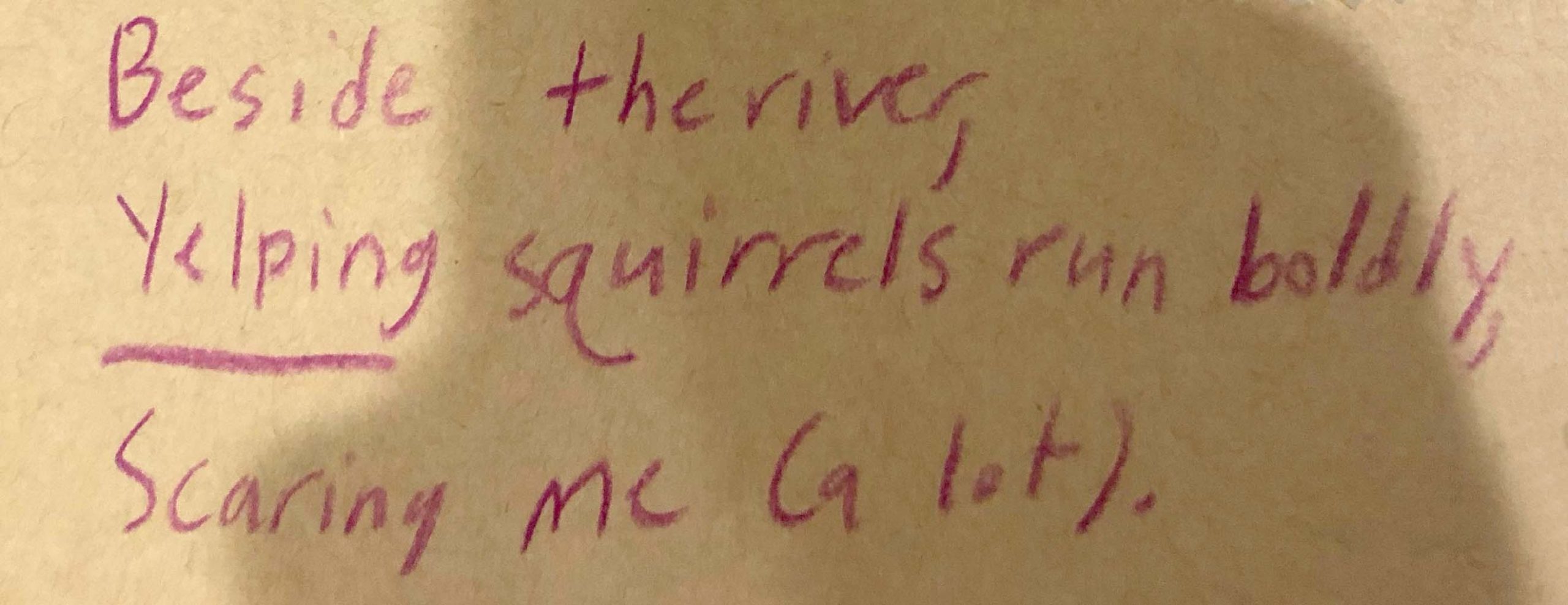

Some students are not ready for the pencil right away. Some students need to remediate old habits. Students should first work with the touch and trace cards and the sand tray learning and practicing the strokes of each letter. Once you have built up this skill, slow focused strokes and stamina you can move to pencil and paper. We add in line and maze work as well. This may seem unnecessary but it will help students see the effects of pressure, position and speed on their line. A tip is to have the student change colors each line, which will help the student slow down and foster focus. For the line work in Volume 1, or the maze work in Volume 2, consider using transparent paper so your student can use the mazes more than once and increase their fine motor skills. On p.19 we give tips to painless or interactive journaling. Try to make writing playful, asking questions, listening, making observations, discussing, taking a “my turn” and “your turn” approach to learning.

~Clare