How do we get students excited to write a sentence?

I’d start the lesson with this whopping fact:

Every year more than a SEPTILLION snowflakes fall on Earth. Hundreds of inches of snow falls on the Sierra Nevadas here in California alone! Septillion is a cardinal number—a “quantity”—that’s represented by the numeral 1 followed by 24 zeros. One septillion is a very BIG number!

I’d follow this with some smaller, yet still amazing facts:

Snow is made up mostly of air:

Fresh snow contains a bunch of trapped air, which is why it feels light and fluffy.

Snow is frozen water:

Snow is simply water vapor that has frozen into tiny ice crystals in the clouds.

Snow can fall even when it’s not very cold:

As long as there is enough moisture in the air, snow can fall even at temperatures slightly above freezing.

Snowflakes are six-sided and unique:

Depending on the temperature and humidity, and because each falls through the air differently, they have unique patterns and six-sided shapes—needles, columns, and plates.

Close the lesson with another BIG fact:

The biggest snowflake, recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records back in 1987, was found in Montana. The snowflake was 15 inches in diameter and 5 inches thick! That’s one BIG snowflake! I’d likely mock up a way to help them see this fact:

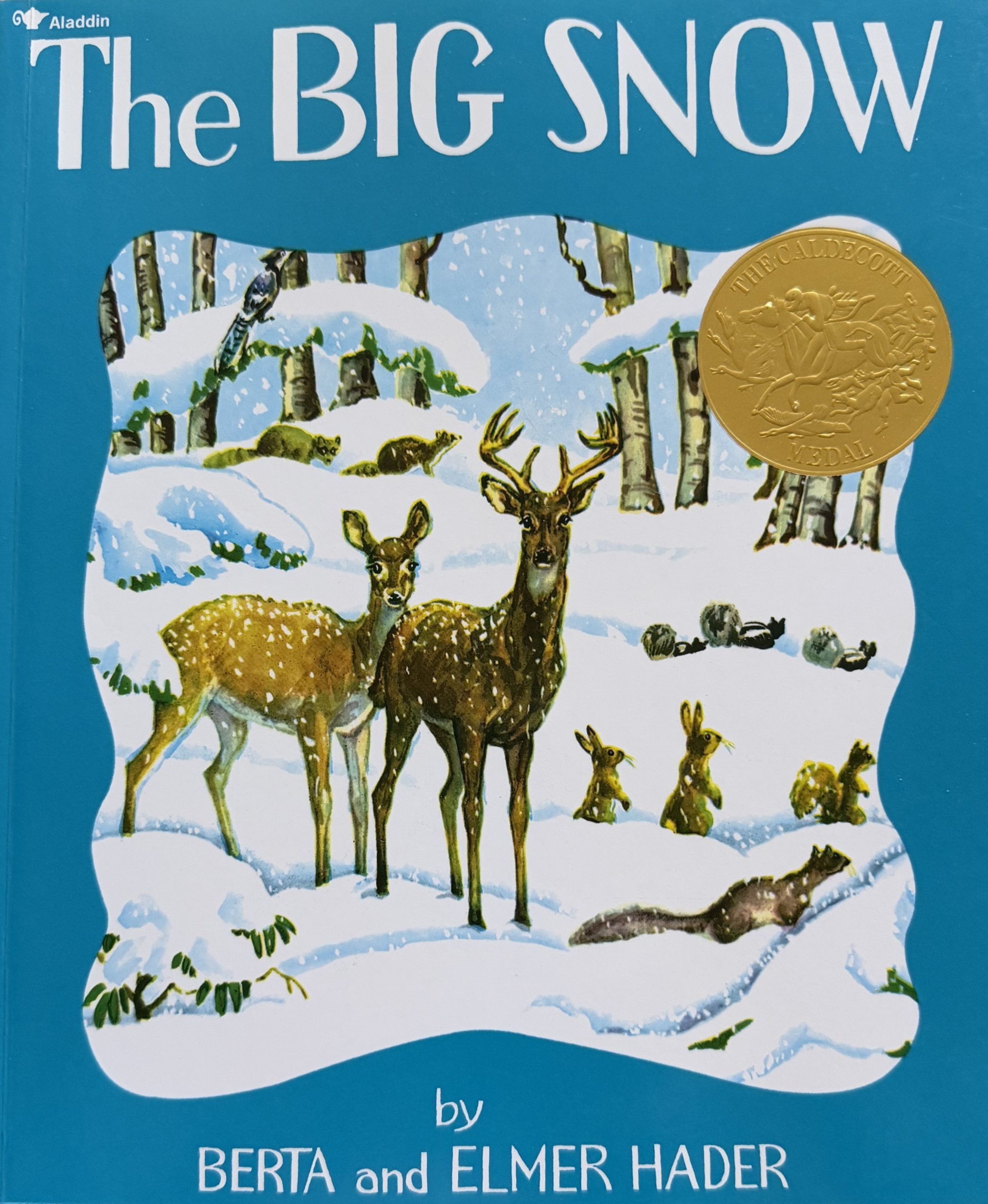

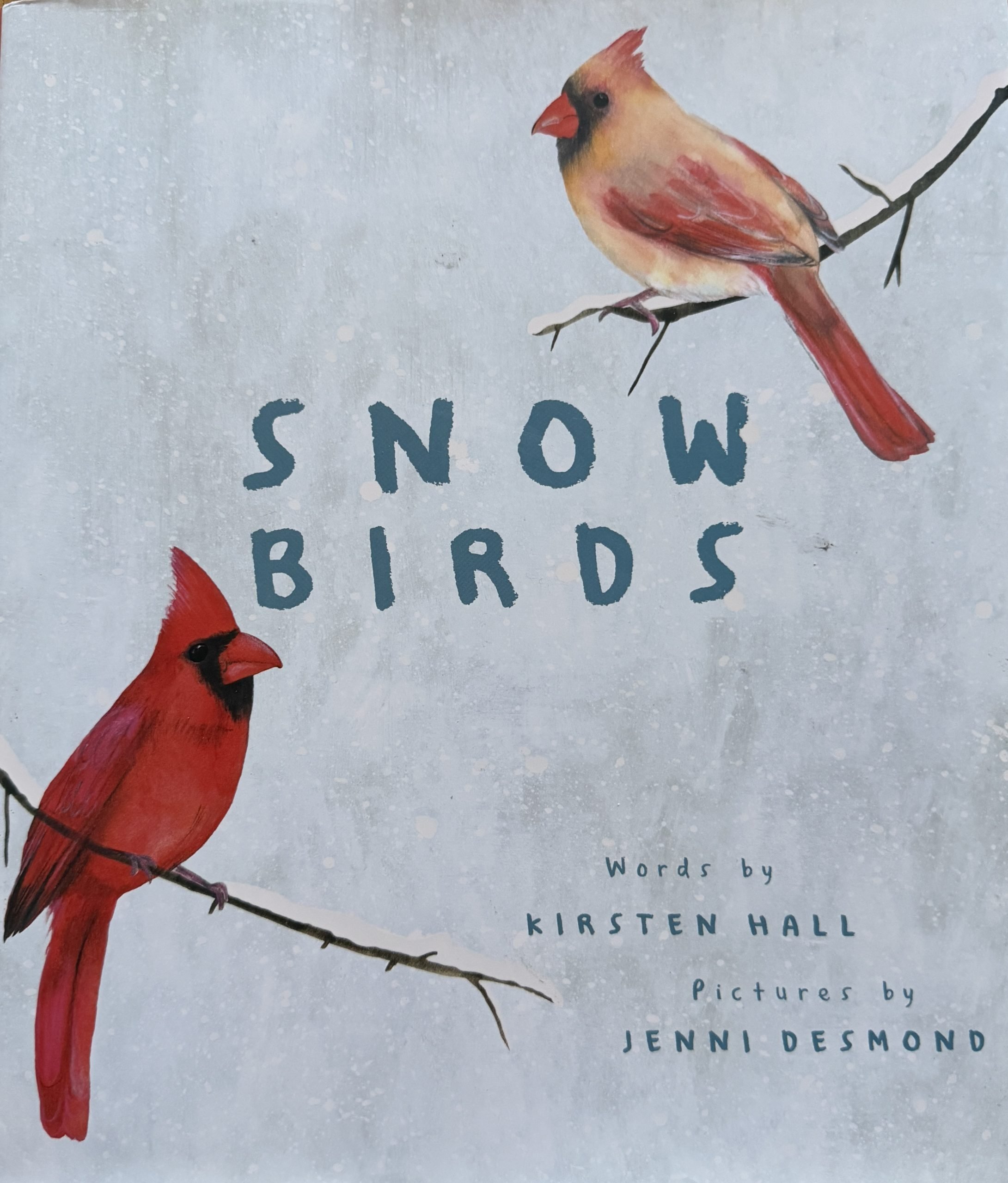

Next, I would read some wintry books. Here are some favorites:

The woodland animals were all getting ready for the winter. Geese flew south, rabbits and deer grew thick warm coats, and the raccoons and chipmunks lay down for a long winter nap. Come Christmastime, the wise owls were the first to see the rainbow around the moon. It was a sure sign that the big snow was on its way.

The woodland animals were all getting ready for the winter. Geese flew south, rabbits and deer grew thick warm coats, and the raccoons and chipmunks lay down for a long winter nap. Come Christmastime, the wise owls were the first to see the rainbow around the moon. It was a sure sign that the big snow was on its way.

Here we’d think about winter taking place in the natural world. We’d explore the four seasons, focusing in on winter. As the animals watch fall slipping away and prepare for winter, students will follow, learning important information along the way.

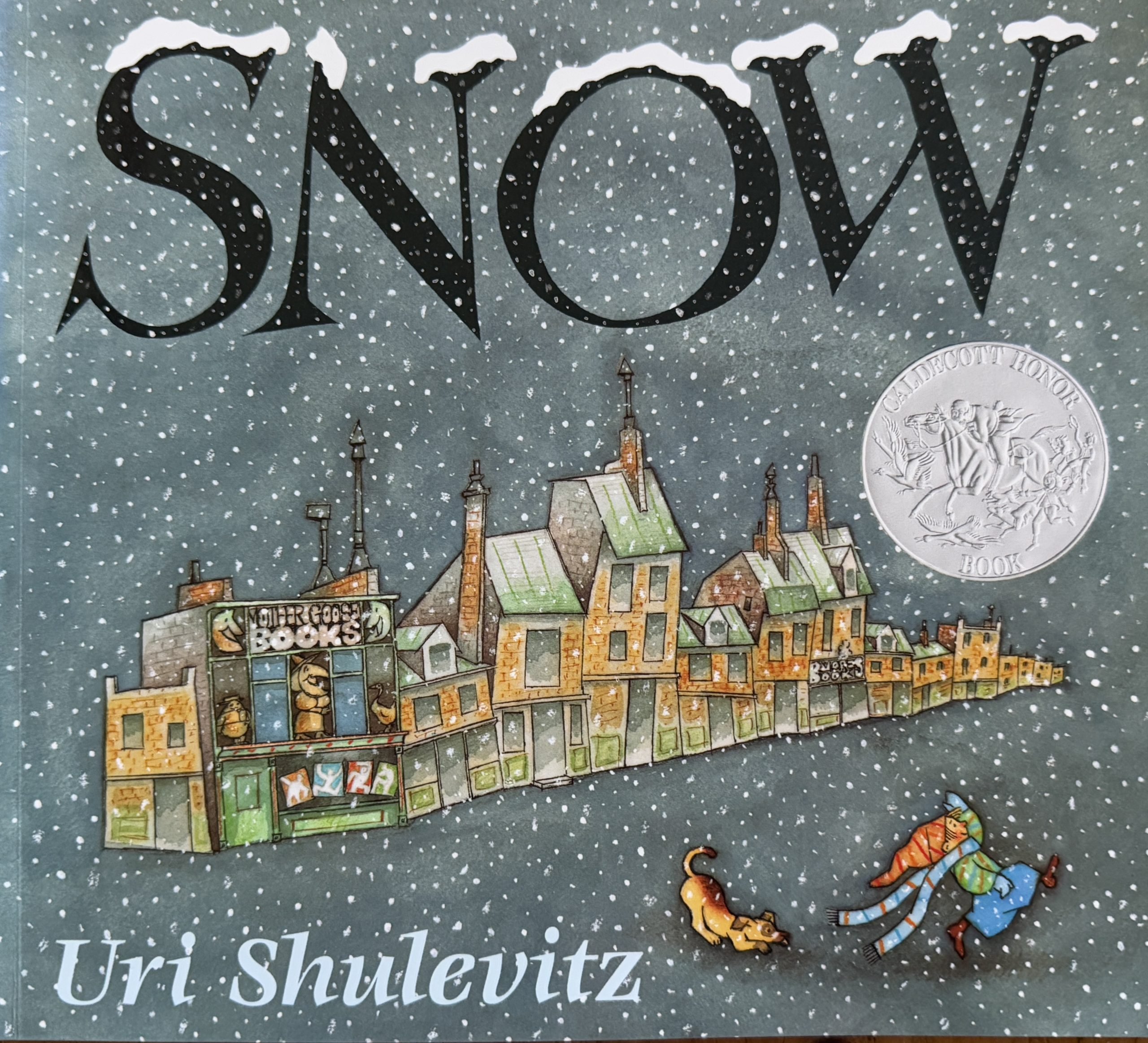

No one thinks one or two snowflakes will amount to anything. Not the man with the hat or the lady with the umbrella. Not even the television or the radio forecasters. But one boy and his dog have faith that the snow will amount to something spectacular, and when flakes start to swirl down on the city, they are also the only ones who know how to truly enjoy it.

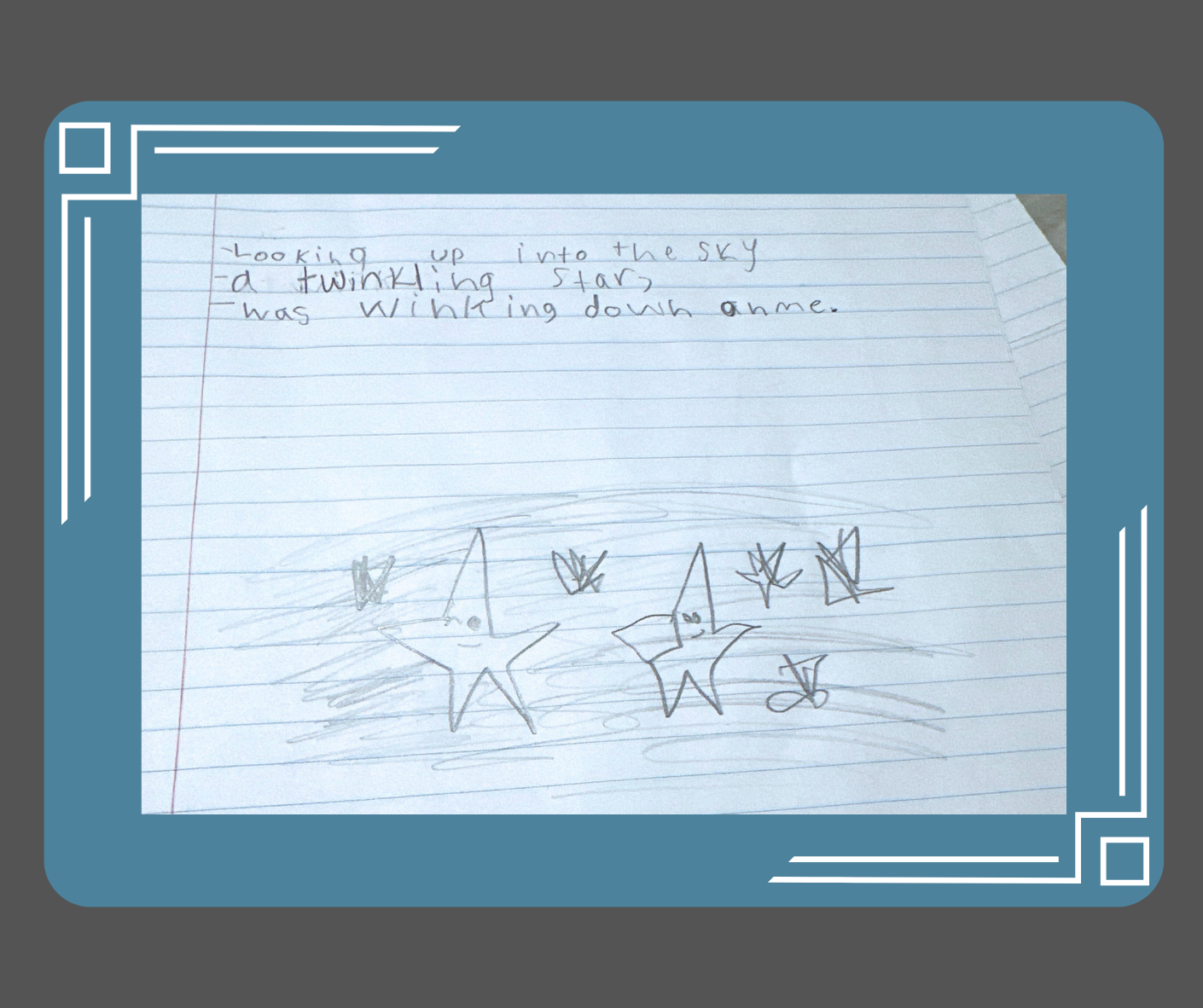

Now it would be time to write: “This wonderful book begins with three short sentences.”

The skies are gray.

The rooftops are gray.

The whole city is gray.

These sentences have one word in common: gray.

We have set the stage, ignited curiosity, and offered some really intriguing fodder. Now I’d get into the lesson:

There are four types of sentences:

Declarative sentences give, or declare, information.

Imperative sentences give commands, make requests, or implore.

Interrogative sentences ask questions.

Exclamatory sentences express strong emotions.

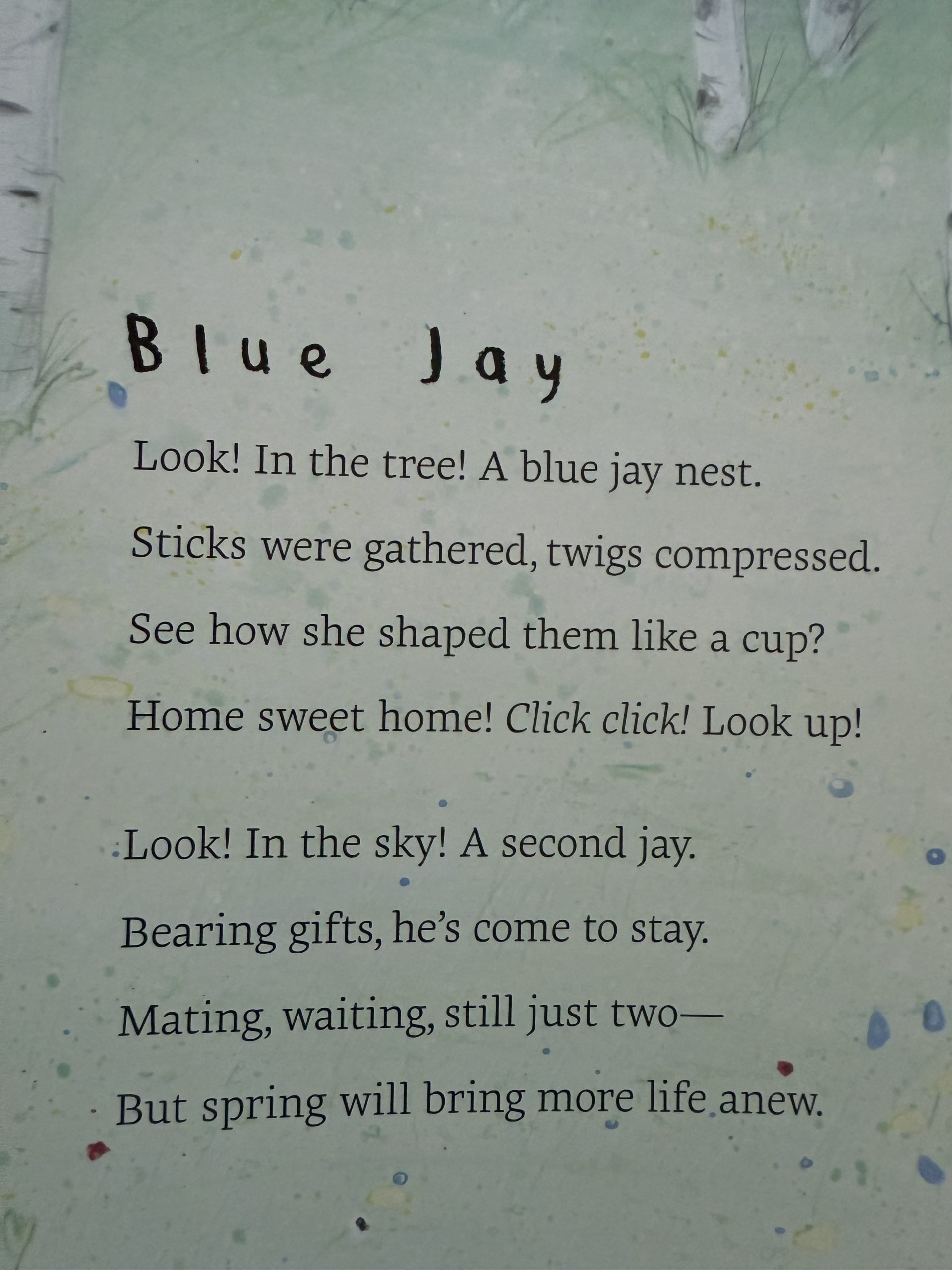

Here I’d pull out another book. This one is a book of poetry, but not just any poetry, these poems are focused on the tenacious birds who stay put in wintry conditions.

We will read several poems together, learn about specific birds, then we will focus in on the blue jay. We will read about the blue jay in the appendix at the back of the book before focusing in on the poem. We will learn that these birds store up to 100 seeds and nuts per day in preparation for winter. We will learn about its tricky ability to hide the store and locate it easily when needed. We will learn about courtship and nest building and the raising of baby jays. This and more. And then we will read the poem.

First we will notice that the poem is two stanzas. Then we will notice something wonderful: All four types of sentences are woven here! We read aloud. As we read we hear the tight rhythm, we hear the perfect rhyme. Isn’t poetry grand?

But now it’s time to craft some snowy sentences, and before the magic slips away, I’d remind my students: Sentences are POETRY!

I would help my students get started (you can too!):

I’d write on the board: In winter…

I’d ask: “What next?”

The student might write:

In winter, animals are hungry.

I ask: Which animals?

In winter, chipmunks and owls and deer are hungry.

I ask: What will they do?

In winter, chipmunks and owls and deer are hungry, so they collect and store food away for the coming snowy days.

Now that is a sentence,” I say to them! That is a sentence that is like a poem:

In winter

chipmunks and

owls and

deer are hungry,

so they collect

and store food away

for the coming

snowy days.

~Kimberly