Tip #5

Tip #5

Writing is a gift.

I’ve been teaching the art of writing for over 30 years. I DO NOT insist my students wrangle a lasso to subdue their grammar. Remember, Form follows Function. I DO insist they value their ideas, and engage in the art of communicating authentically. I tell them:

Wrap your idea like a gift you would like to receive.

Would a beautiful gift be wrapped in sloppy handwriting? Would it contain run-on sentences with no end marks e-v-e-r? Would it be tedious to read with holes in the flow that confused the reader?

I don’t think so!

I tell my students: Your writing is a gift!

When it comes to learning language arts much of the exceptional work that your students will accomplish is subjective in nature tied to their ideas. As we moms and teachers value these ideas and challenge them to catalog and craft these ideas over time, literacy skills soar.

Ideas spring from a wealth of knowledge tied to curiosity. During the elementary years students from grade 3 through grade 8 will read 36 (yes, THIRTY SIX!) novels! Their discoveries from reading tied to their observations and inspired by imagination and curiosity will enable them to engage in the weekly writing exercise—a simple paragraph communicating an idea unique to the writer. Students will compose 144 paragraphs. What is unique about our approach is that the paragraphs being composed will be meaningful to the writer. Unique. Authentic.

Each of our Literature & Writing Discovery Guides is designed to guide students into the art of reading and writing and thinking. But there is an added bonus, Section 5. Please don’t skip Section 5!

Section 5 sets aside a week to think about, absorb, and apply the story as a whole. The goal of Section 5 of is to create a project to remind readers that stories are gifts that keep giving.

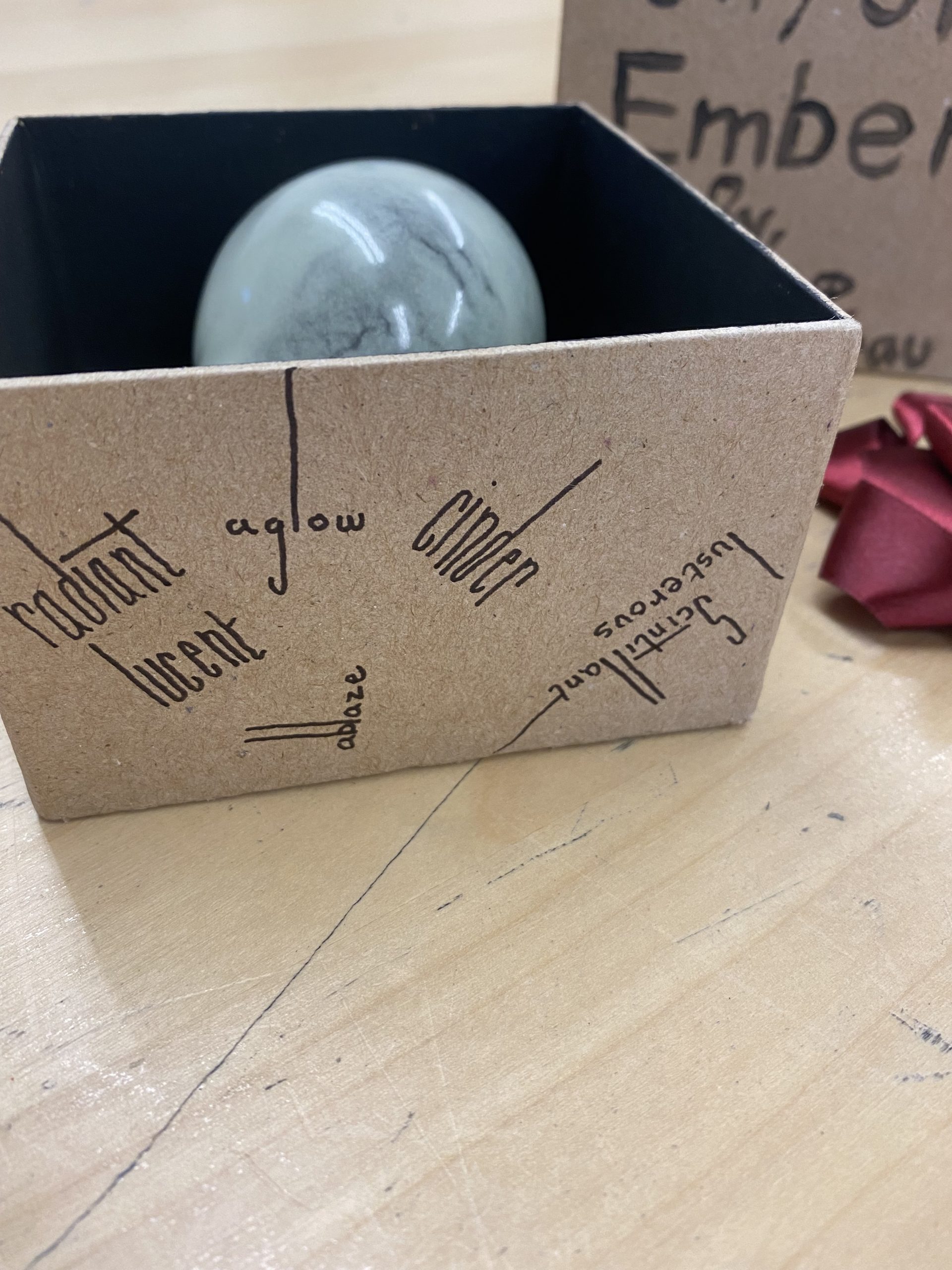

This project is tied to the story City of Ember by Jeanne DuPrau. This student used singular words related to the story, themes, and quotes to decorate the outside of a little box. Inside they found an object—a lightbulb vase—and filled it with glow-in-the-dark paint to visually represent the conflict of the story:

What will happen when the generator finally fails?

I love this little project. I love the story City of Ember. The takeaway for this teacher: If we were to reduce writing to mere mechanics, darkness would fall on ideas and we would be sorry readers!

Let then write ideas!

~Kimberly

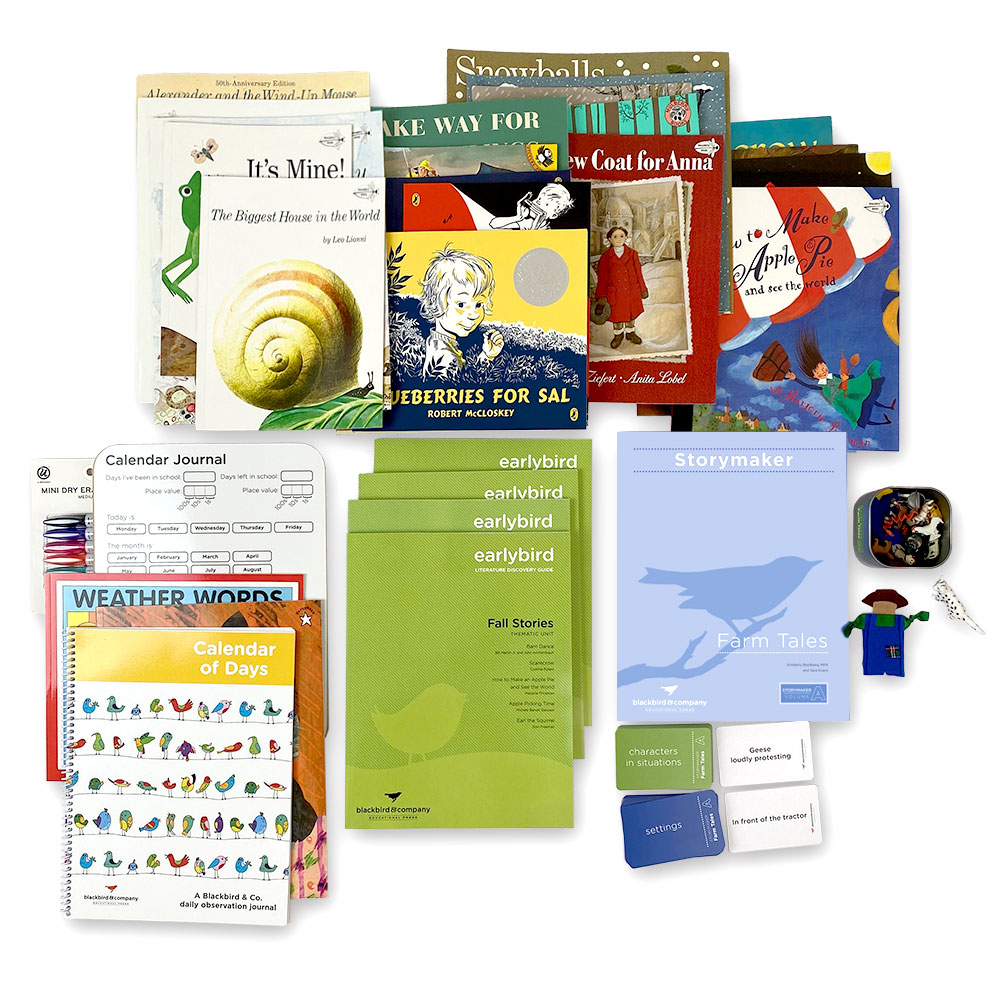

For those of you who are new to Blackbird & Company, and those who are seasoned users, pull up a log, and gather round the campfire!

For those of you who are new to Blackbird & Company, and those who are seasoned users, pull up a log, and gather round the campfire!