Campfire Tip #10: One Bite at a Time

“The only way to eat an elephant is one bite at a time,” or so the saying goes.

That’s also the mindset one must adopt when tackling the year-long research essay, known as Essay Volume 6: Advanced Research. This unit is designed for 11th and 12th grade students, representing the culmination of their research and literary writing skills.

This school year marks my first foray into teaching Essay Volume 6. Over the last two sessions, I’ve learned a lot—and I’ve also fallen in love with this essay unit! It teaches life skills and writing habits that will stick with students for years to come.

Is Essay Volume 6 a good fit for your student, either this coming year or years down the road? Here are some of my takeaways from teaching the long research project:

1. How It Works

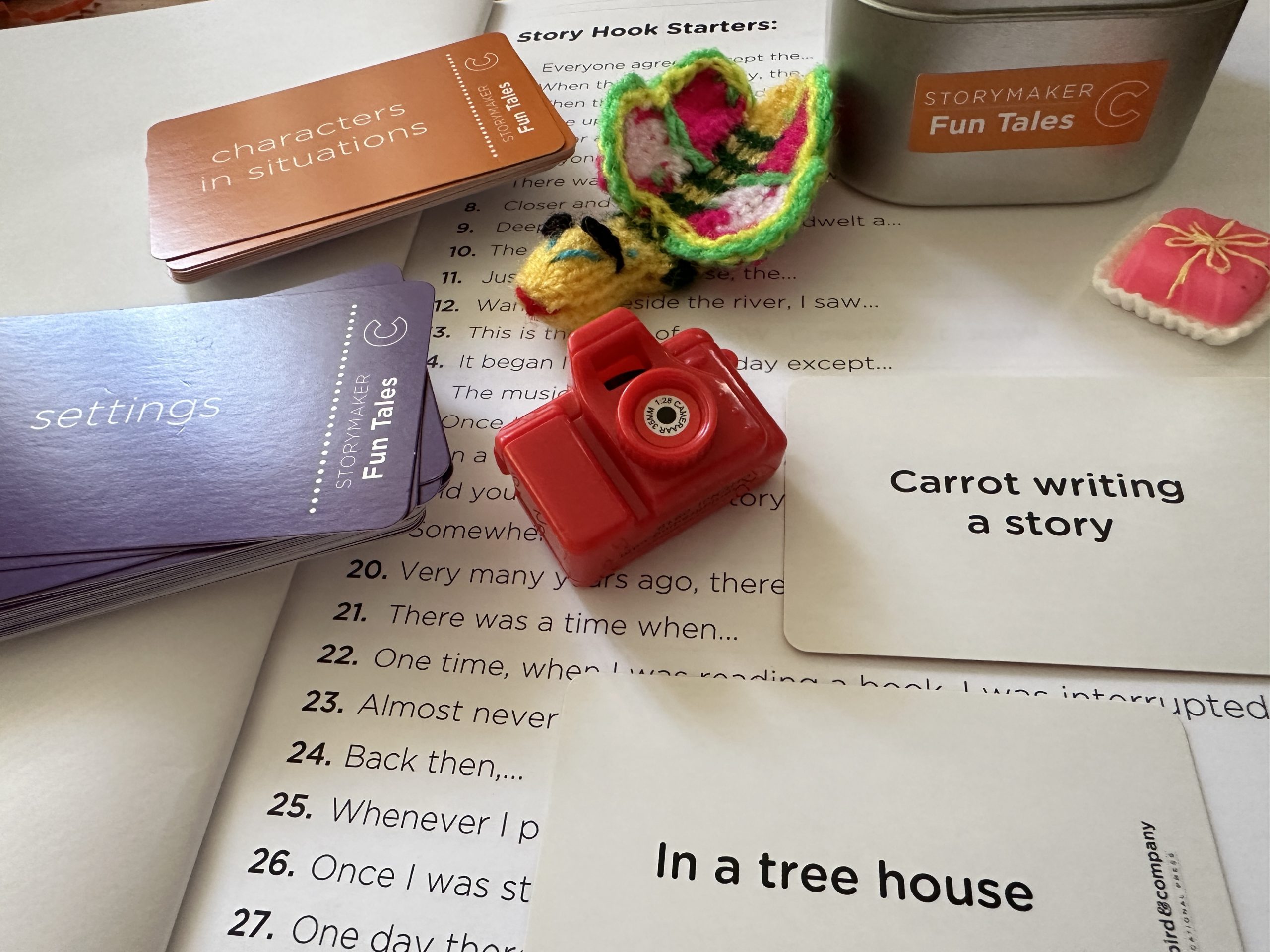

Before we get into WHY I love Essay Volume 6, let’s go over what this unit entails. The Long Research Essay can be organized into two parts: the research process and the writing process. And conveniently enough, the guides are broken down into A and B volumes along the same lines.

In the first half of the project, students choose a person, place, and thing they want to learn more about, unifying the three topics with a single theme (like creativity, truth, perseverance, or tragedy). Then they take a self-directed tour through the library and internet to find their sources and build a fund of knowledge. As I’ve taught this Pages class, I’ve given lessons on how to find and use credible sources—which is one of the most important skills in college writing—and expect students to present their research findings each week. This stretches their abilities in new ways!

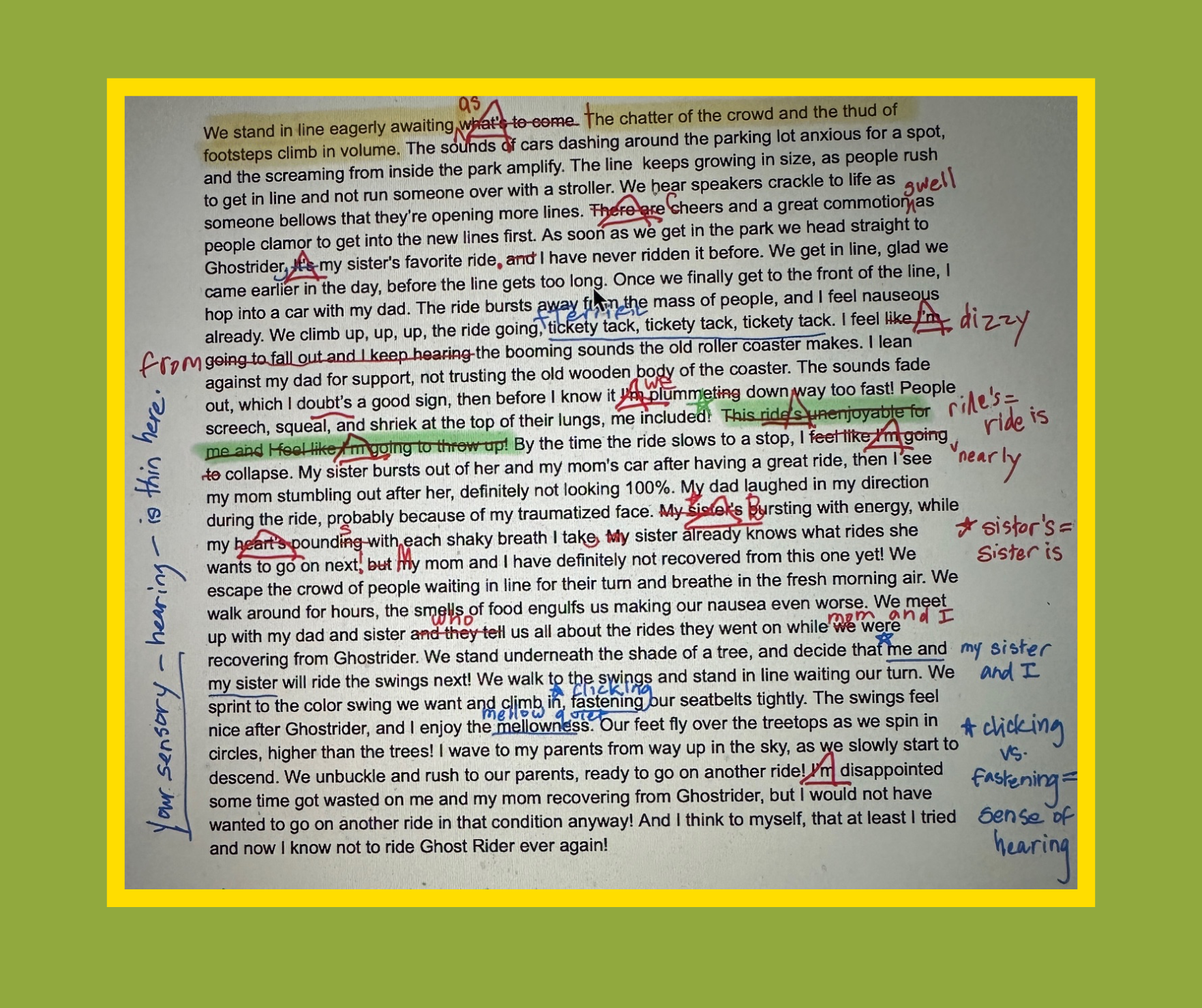

In the second half of this course, students synthesize their research by writing and revising. Because they combine their person, place, and thing with their theme, they create a brand new narrative about their topics—chances are, no one has combined their topic and theme in the same way before! This is an exciting opportunity to apply a literary essay style to one’s own research.

2. Motivated Learning

A major principle of the psychology of memory is that we remember information that’s personally meaningful to us and struggle to remember information we don’t care about. You probably know this just from living life.

Because Essay Volume 6 gives students so much creative freedom, they can choose to research topics they’re passionate about, transforming a potentially mundane research project into a motivated pursuit of knowledge. Writing doesn’t have to be boring. If you’re writing about the right things, it can be the most engrossing activity imaginable.

For example, my student, Kingsley, has long been inspired by ballerina Margot Fontayne. She has a book about Fontayne’s life on her bookshelf that she’s never had the time to read. But Essay Volume 6 says, “Pursue your interests!” So that’s what Kingsley’s done. Choosing Margot Fontayne as her person to research, she’s taken a dive into this legendary dancer’s life, satisfying her curiosity and honing her research and writing skills. She finally had the chance to read her book!

When done right, research writing gives thinkers the chance to pursue questions they have about the world.

3. Rising to the Challenge

Time and time again, I’ve seen this truth play out: Set high expectations and students will rise to meet them.

The Long Research Essay is a daunting task. It demands self-discipline. Motivation. Consistency.

But, I believe our Blackbird students are more than up to the challenge. When students set big goals for themselves and then achieve them, they build their confidence one brick at a time. The impossible becomes possible. Students learn that they are capable!

The week-by-week scaffolding of Essay Volume 6 provides the framework necessary for students to soar to great heights. You don’t craft a masterpiece in one sitting; rather, you chip away at your work of art day by day, sometimes fueled by perseverance rather than inspiration.

Let’s set some lofty goals. And then get to work.

~Claire S.

Campfire Tip #12: Be like Leonardo

Campfire Tip #12: Be like Leonardo