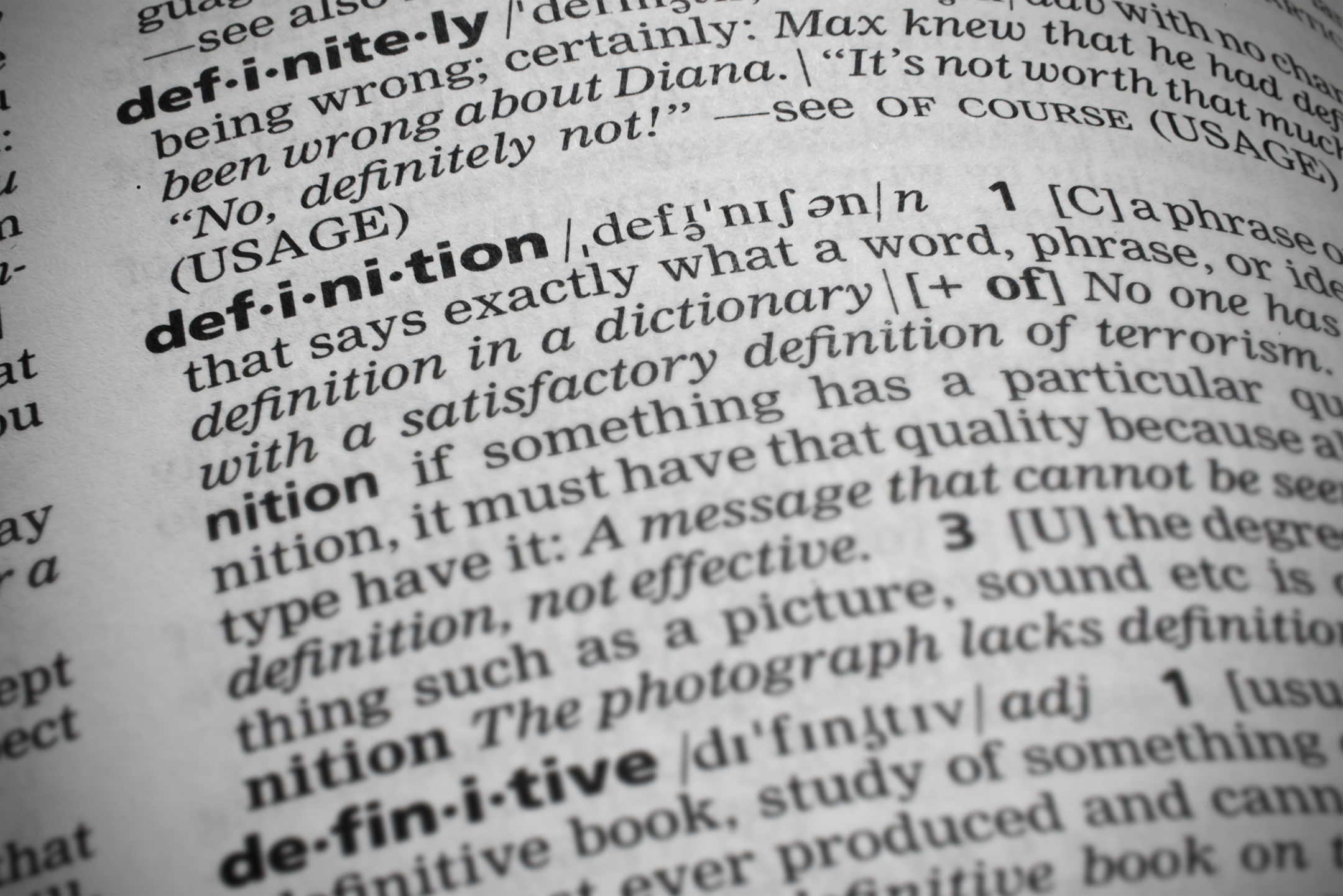

Exploring vocabulary is so much more than an activity to check off the list! Words are the building blocks of language, are what we humans use to communicate our ideas, and each one holds certain specificity.

Specificity is a pairing of the word “specific” (clearly defined) + the suffix “ity” (quality or state of being). So, this word, which arrived on the scene via the French word spécifique back in the 1600s, means to hold a special quality.

With this in mind, using a handheld dictionary becomes an adventurous treasure hunt. Students working in our CORE Literature and Writing Discovery Guides will, each week, explore a handful of singular words from the week’s reading. There are many skills embedded into this complex activity beyond the obvious, vocabulary development. The act of searching for a word in an alphabetized catalog reinforces spelling skills, strengthens the ability to problem solve, and fortifies focus. Of course, this process of working for meaning and applying new knowledge, more than anything else, sets this word into stone in the mind’s eye, and places it into a growing treasure chest of words.

This student, who was working in a Level 2 unit tied to Inside Out and Back Again, did a terrific job looking up each word in a held-by-hand Oxford English Dictionary. All of the definitions were copied accurately. Next came the difficult part, using each new word in a new way.

By the time students reach this level (4th and 5th grade), they have worked through Earlybird and Level 1 units and have had this exercise modeled for them. Still, using a word in a new context is a really difficult writing skill. But it is a skill that will empower students to write their ideas with specificity!

Notice the way this student used the word “flecked” below. Even though the definition of the word is correct, the sentence demonstrates the meaning has been confused with the word “flicked” meaning to propel something with a sharp movement. One way to support the student, is to provide an example: flicked the flecked stone. Another trick, is to send the student back to the dictionary to copy the phrase that is used to demonstrate the word in a context. Here the phrase was: whitecaps flecked the blue sea. Encourage the child to craft the phrase into an original sentence. For example: Yesterday at the beach whitecaps flecked the blue sea.

Here’s a peak at the Vocabulary Section from our Level 2 Guide tied to Because of Winn Dixie completed by an end-of-year 4th grader who is delightfully engaged in the treasure hunt and confidently using new words in golden ways!

Using our Earlybird through Level 3 CORE Literature and Writing Discovery Guides, students will explore more than 100 words per year, adding significant treasure that possesses specificity. This will serve them well as they engage in the work of constructing their ideas!

~Kimberly