“So many things have gone out of date. But after all these years, words are still important. Words are still needed by everyone. Words are still needed to think with, to write with, to dream with, to hope and pray with. And that is why I love the dictionary. It endures. It works. And as you know, it also changes and grows.” ~Mrs. Granger, Frindle

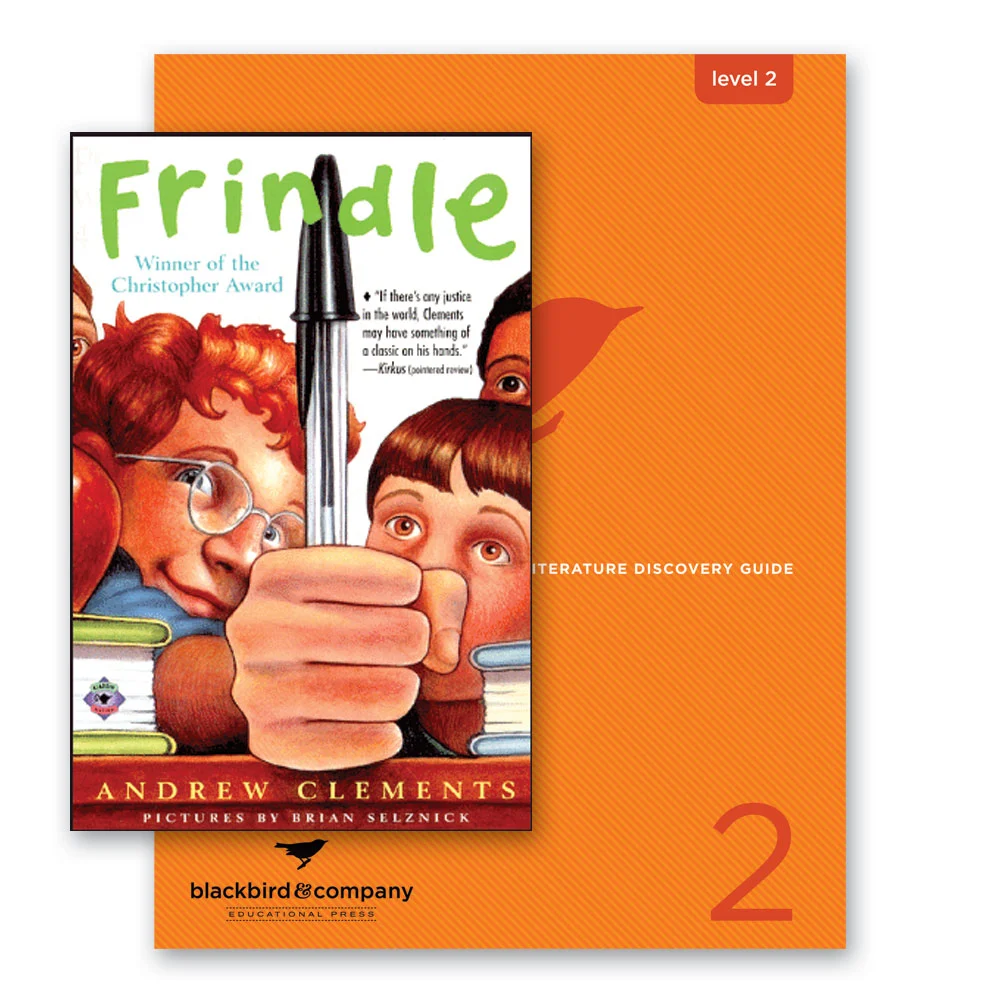

Recently during a Pages Level 2 CORE Class, we explored Frindle, by Andrew Clements. The above quote was offered by Mrs. Granger, Nick’s, 5th grade teacher. Mrs. Granger has quite the reputation for the laser eyes, no messing around, lots of homework and her great love of words. Mrs. Granger has 30 dictionaries in her classroom and one massive one that takes center stage. Her battle cry is, “Look it up! That’s why we have the dictionary.”

The students in my class, similar to Nick, expressed a dislike for Mrs. Granger’s style of teaching. But they also shared a dislike of the dictionary. They didn’t enjoy looking up words and thought of it as chore. We started off the beginning of class by sharing dictionaries we used at home and suggestions for new ones. It had us looking up facts before you knew it!

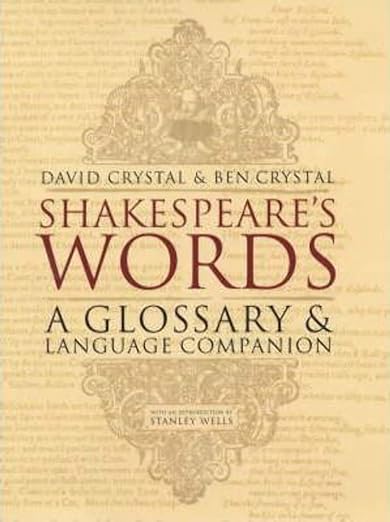

During the first class we learned a ton from Nick’s report on dictionaries! Many people thought that the first English dictionary was put together in the 1700’s by a man named Samuel Johnson. But there were dictionaries before this. The things that were different about Johnson’s dictionary was the size. He included over 43,000 words! He chose words he thought were important and gave many examples on how they were used. The word “take”, for example, can be used 113 different ways! All of this prompted me to look it up the largest dictionary in the world, the Oxford English Dictionary, which comes in 12 volumes and contains 415,000 words!

In every one of our CORE units, we offer a list of vocabulary to look up in each section, usually 5-6 words. Typically, we infer meaning of words from context when reading. But ask a student, or adult for that matter, to tell you what that same word means, and we usually encounter struggle. Looking up a word helps us truly learn it and then be able to use it within our daily language or writing. We offer example sentences for your student to learn from in our Answer Keys, plus the sentence where the word is used by the author in the book. And we always point our students to the hand-held dictionary. The dictionary, as Johnson started, will give example sentences along with the definitions. These are useful to point out.

We also offer Operation Lexicon, which assigns the student daily vocabulary from exceptional writers, like E.B. White or Ted Hughes. The student will read words used by an author and how the word is used in their writing. They will explore the definition and then craft their own sentences. The week ends with students choosing their favorite words learned and using them in a micro-story. We will offer Operation Lexicon Pages classes every year and go through these exercises with the students online. Once, I challenged my students to find another definition of the words given and then use the word multiple times in their micro story demonstrating the different meanings. It was quite fun! While talking with one of my past students I was delighted to learn she still used this challenge in her micro-stories.

“At time it felt like even the buntings were laughing at her (they probably were, buntings are crude and obnoxious creatures).”

“Gustavo hated all of the bunting and festivities of the circus, for it was truly nothing more than a prison for poor, kidnapped animals.”

We often discuss words we made up in our families, words we have used over the years, words that are gibberish but we know mean something. You know the words that are said over and over and after a while, we accept as words? “Pank” for pancake, “squishly” for the soft toy. The examples are endless. These are the familial words we know but the outside world might not recognize, words that are not in the dictionary but have meaning because we decide they do!

In a recent Pages Poetry class, we learned fun facts about Dr. Suess, then created found poetry and pastiche poetry. We then Dr. Suess’s poetry to spring into poetry of our own. We challenged our students to use two of Dr. Suess’s made-up words in their poetry. Something Dr. Suess was quite good at is inventing words, creative language and rhyming schemes. We had fun using words like: beczlenuts, hoobub, kwuggerbugs, thanders, sneedle, glikker, wumbus and yuzz.

There are also words that are frowned upon, words we are asked not to use when we are children but are words with meaning all the same. Nick points out the word, “ain’t” is not an approved word by most grown-ups but you can find it in the dictionary. I was told growing up that “ain’t” wasn’t a word. I was asked not to use it because it was not proper English. I had never looked up the word as a child, but now I sure am motivated! I learned that the word is defined as, am not: are not: is not or have not: and has not. I found this really interesting as I am teaching one of my children to use contractions this week. At the bottom of my dictionary there is a note.

Hint: Most people feel ain’t is not proper English. When you are trying to speak or write your best you should avoid using ain’t. Most people who use “ain’t” use it especially when they talk in a casual way, or in familiar expressions like “you ain’t seen nothing yet.” Authors use it especially when a character is talking to help understand what the character is like.

Even as I write this the spell check wants to tells me “ain’t” is wrong and give me other word suggestions!

“Who says dog means dog? You do, Nicholas. You and I and everyone in this class and this school and this town and this state and this country. We all agree. We decide what goes in that book.”

~Mrs. Granger-answering Nicks question on how a word becomes a word.

In Chapter 12 of Frindle, it brings up the belief of many that the word “quiz” was made up in 1791 by a Dublin theatre manager named Daly. He bet someone that he could invent a brand-new word in the English Language and chalked the letters q-u-i-z onto every wall and building in town. The next day, and throughout the next week, people all over Ireland were wondering what it could mean. Quiz was the only English word invented by one person for no particular reason. I confirmed this story on the internet! Doesn’t this get you curious about words?

Sure enough, my students who do not enjoy using the dictionary tried looking up the word “frindle” because they were curious if it was a real word you could find in the dictionary. Sadly, it was not there. This confirmed it is a great made-up word for this fictional story. This inspired me to do more internet searching! How many words are added to the dictionary each year? I was surprised to find that an estimated 800 to 1,000 new words are added each year! Frindle might one day become one of those words.

Words, words and more words!

By the age of 5 years old children recognize at least 10,000 words. By 10-years old children can speak and write an average of 20,000 words and learn on average 20 new words a day. They can understand that words have multiple meanings. A High school student may know anywhere from 25,000 to 50,000 words. When I looked up the average vocabulary for adults it was a range from 20,000 to 35,000 words. Wow. If most 10-year-olds can speak and write an average of 20,000 words and some adults average a vocabulary of 20,000 words, what happened? Did the learning of words stop? Why do we stop being curious, intrigued, and playful with words?

One of my students came to class once and shared that in the publication, The Week Jr., Frindle was listed as one of the Number 1 Most Read Books in New Hampshire.

In my Pages classes, I always introduce the author of the book. Frindle, was Andrew Clements first novel. He began trying to write the book in 1990 and it was eventually published in 1996. I like to give timelines when I can because I think it demonstrates to students that writing, editing, actually having something published takes time. Frindle became more popular than any of his books before or since and turned Andrew Clements into a full-time writer.

Sometimes kids ask him how he has been able to write so many books::

“The answer is simple: one word at a time. Which is a good lesson, I think. You don’t have to do everything at once. You don’t have to know how every story is going to end. You just have to take that next step, look for the next idea, write the next word.”

~Clare