“If you want your children to be intelligent read them fairy tales. If you want them to be very intelligent, read them more fairy tales.”

~Albert Einstein

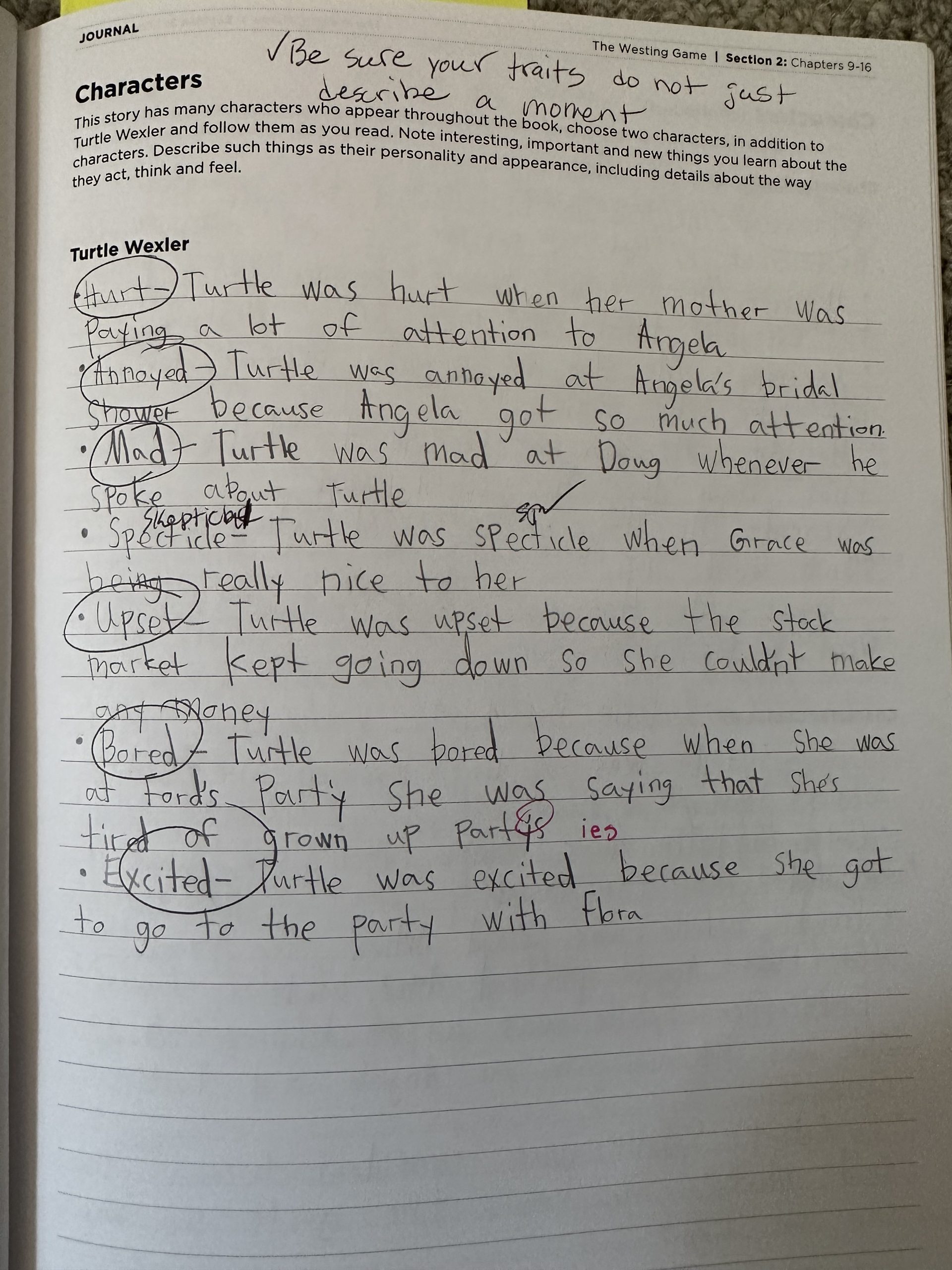

I recently came across some of my daughter’s old writing. I believe she wrote it when she was 12 or 13. She is now 15 and a sophomore in high school. She was answering the prompt: “Why is writing important?” She learned that writing is more than just words on a page, it’s how people express how they are feeling. She believes for writers it’s like painting a blank canvas.

Words help us learn and feel or maybe better said, to learn how to feel.

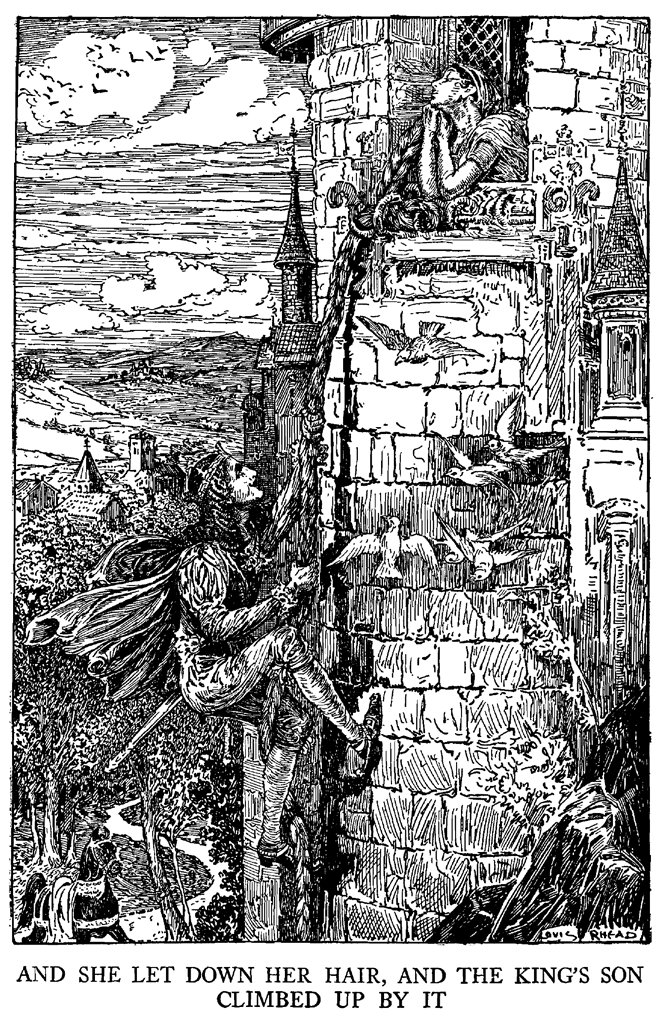

The other night I read to my son Grady before bed. We read one of Grimm’s fairytales, “Rapunzel”. Grady lay fully cocooned in his blanket, over his head, listening. As you probably know Rapunzel was taken from her family as a punishment for stealing the green, leafy, vegetable, rapunzel, from their neighbor’s garden. The garden belonged to a very powerful and wicked witch. The girl, Rapunzel was raised by the witch and was sent away from all people to live in a tower she could not escape, all alone. A prince heard her singing from the tower. He watched the witch visit her and saw her let down her long hair for her to climb. He did the same and soon after many months got to know Rapunzel and they fell in love. The witch discovered that the prince was visiting. She cut Rapunzel’s hair and then sent her far away, alone in a desert. The witch hung Rapunzel’s hair at the tower and let the prince climb up, but once he did, she was there to greet him. She scared the prince from the tower into a thorn patch far below, where the prince’s eyes were torn out. He wandered for years blind and alone until he wandered far enough. He found Rapunzel at last, drawn by her beautiful singing. This fairy tale ends well with the prince being reunited with his love, Rapunzel’s tears healing his eyes and them living happily-ever-after back in his kingdom.

Whenever I read Grimm Fairy tales to my children as they were going up, I always wanted to change what happened. I would naturally edit—the prince losing his eyes and wandering alone, the wolf eating Grandma. What I started to realize over time is that children, like being scared. But there is a difference being scared by books versus movies or television. With books readers can take it as it comes, with language aimed at a child’s imagination, suspense and simple elements building the world of the story. What if it’s actually important to hear that bad things can happen? We can feel pain. We can get hurt. We can become resilient human beings.

Sometimes in life, in many ways, we wander blind for a period before we find the good, before we can see.

I want stories to end well. I want to eliminate the scary in the world because I don’t want to acknowledge the fear, I feel for my children in the world we live in today. As my daughter wrote so eloquently, these stories have taught me how to feel.

I recently read an article about the importance of being scared. Einstein was quoted: “If you want your children to be intelligent read them fairy tales. If you want them to be very intelligent, read them more fairy tales.” The intelligence that Einstein is referring to is existential intelligence.

Existential intelligence is defined as the sensitivity and capacity to tackle deep questions about human existence, such as the meaning of life, why do we die and how do we get there. The skills are reflective, deep thinking and design of abstract theories.

I saw an interview with President Obama years ago who discussed his great fear for young people losing this ability to be deep, reflective thinkers. In our fast-paced world we are encouraging more and more people to skim through reading material on electronic devices and not to sit and contemplate deeper meaning in what they are reading. In retelling Hansel and Gretel, nearly a century later, author Neil Gaiman asserts:

“If you are protected from dark things then you have no protection of, knowledge of, or understanding of dark things when they show up.”

The great polish poet, Wislawa Szymborska, wrote a reflection on the first edition of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales which revolutionized storytelling:

“Children like being frightened by fairy tales. They have an inborn need to experience powerful emotions.”

Andersen took children seriously. He speaks not only about life’s joyous adventures, but about its woes, its miseries, its often-undeserved defeats. Andersen had the courage to write stories with unhappy endings. He didn’t believe that you should try to be good because it pays, but because evil stems from intellectual and emotional stuntedness and is the one form of poverty that should be shunned.

I have realized that throughout my life I have gone to great lengths to not feel or face fear. It’s not just the evil in the world but the great unknown. The what ifs. What if I am not smart enough, strong enough, talented enough, liked, or loved enough? What if I am not good enough?

Children’s author-illustrator Jon Klassen was asked how he comes up with ideas for his books? He says, “It’s just born of fear—of creating. It’s been a way of avoiding something I don’t want to do. And the solution to that avoidance lends itself to a story.”

My daughter went on to say that one of her favorite words she learned more about is the word, dumb. She learned it can mean temporarily unable or unwilling to speak. My daughter has a learning difference. She did not learn to read and write at the same developmental stages as her peers. She often felt dumb, as in stupid or foolish. My biggest fear was her feeling this way. So motivated to protect her and put her in her own tower far away, I kept her out of school and chose the path of homeschooling.

My fears came to reality as I realized I did not make her tower high enough.

The beauty in it all, like in our fairy tales that can be scary, is that we see resilience being born, we see paths that can have obstacles, we see hurts and feel fears. My daughter has been hurt, afraid to try, plagued by words. But she has also grown strong, wise, mature, forgiving and compassionate. Fear comes with gifts. Fear ear can bring us closer to faith. Faith brings hope, in the good, in mankind, in our individual skill sets. Fear and faith seem to go hand in hand and to be sheltered from one keeps us separate from the other. Today, I read to my kids the whole fear filled story of “Rapunzel”. I don’t have to fix stories for them, and I don’t have to fix life. Life is, we are in it right now, and I wouldn’t change a thing, because if I did, I wouldn’t be the person I am today and I happen to like me. Keep reading fairy tales and all stories that end in tragedy. Let your faith be bigger than your fear and enjoy the journey.

~Clare Bonn

Try Douglas Florian.

Try Douglas Florian.

Try Exploring Poetry.

Try Exploring Poetry.