Great essays have the power to encourage, empower, and enlighten. For this reason, essay writing should not be treated as simply a mechanical endeavor, but rather, as a pathway for the writer to communicate the depths of the heart and mind.

Big ideas can be communicated through a range of writing genres in both prose and poetry. It is vital that students discover and explore the potential of all genres. Some writing describes, some narrates, some exposes, and some persuades. Some writing is simply meant to entertain. All writing has the power to inform.

Utilizing our CORE units—Earlybird through Level 3—students will encounter weekly prompts that challenge them to not only write, but also to care about their ideas. By the time they reach the end of elementary, they will be confidently composing expanded paragraphs utilizing many genres including the five big ones: Descriptive, Informative, Narrative, Observational, and Persuasive.

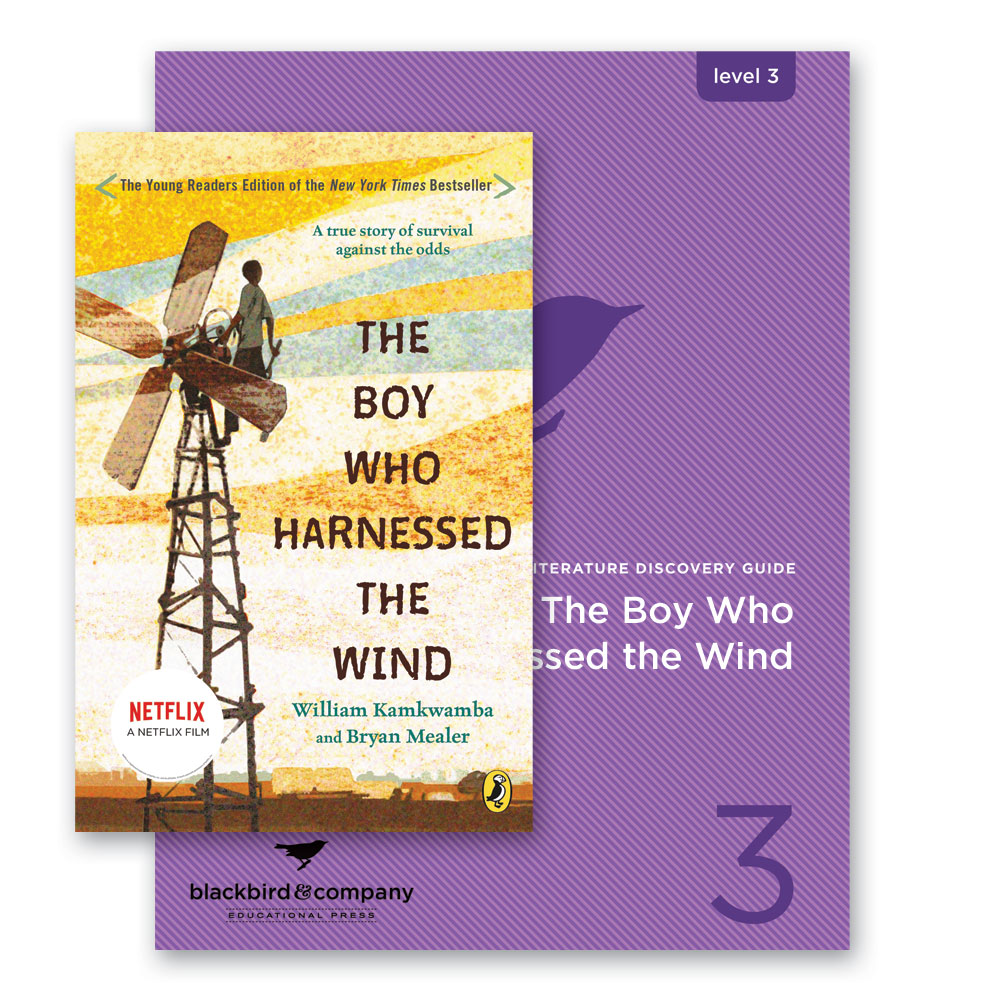

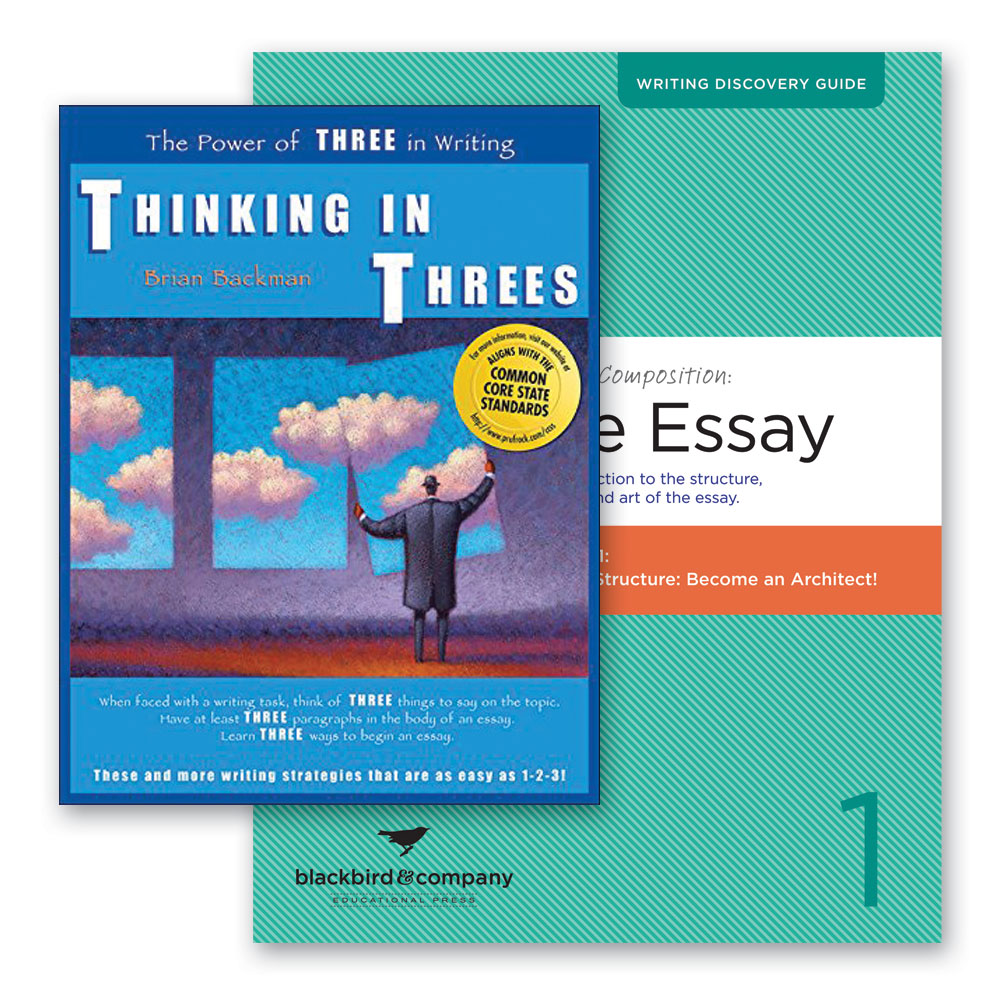

In middle school, as students press into CORE Level 3, they are ready to journey into an introduction to formal composition. We have created three introductory volumes that introduce students to essay form, then guide them into the art of composing the descriptive and the literary essay—both of which integrate an expository element, requiring the student to investigate an idea, evaluate evidence, and develop the idea in a way that is authentic to the writer’s voice and engaging for the reader. After all, producing clear, coherent, and creative writing that captivates the reader is an ultimate goal.

Each of the following units contains five lessons designed to be completed over ten weeks. This said, we’ve built in opportunity for the important work to be slowed down to fifteen, even twenty weeks.

Volume 1 – Essay as Structure: Become an Architect!

Volume 1 – Essay as Structure: Become an Architect!

This exploration of essay form will introduce students to the strategies and stylistic techniques that will enable then to compose authentic essays. Students will not write essays in these five introductory lessons, but rather do a deep dive into essay form, gathering stylistic tools along the way. The word essay derives from the French infinitive essayer meaning “to try” or “to attempt” something. Ultimately the purpose of an essay is to wander through an idea, it is an opportunity to try to communicate that idea within a specific structure. Writers utilized essay form long before educators made the form mandatory, overshadowing the original intent that the form was to shelter an idea and not the other way around! Think of Michel de Montaigne, Francis Bacon, Thomas Paine, Louisa May Alcott, George Orwell, Virginia Woolf—I am certain these great writers were more concerned with the idea to be communicated than the form that would shelter the idea. All you have to do is read an exceptional essay to see this truth—try E.B. White.

When it comes to composing essays, Form Follows Function is paramount!

Writers must focus first on the function or purpose of writing—the idea. Once the idea is drafted in rough form, the writer digs back in and applies mechanics—corrects misspelling, capitalization, punctuation, embellishes word choice, improves syntax, and so on. Writing is a process.

The goal with this first volume is to offer students an understanding of the form, its purpose, and potential, while simultaneously offering exercises that will enable them to elevate their voice in preparation for Volume 2 and 3. Learn to meander through an idea in a constrained manner, explore the role of threes in writing, the HOOK, the THESIS, and much more.

Volume 2 – An exploration of the Descriptive Essay.

During elementary, students have learned to craft expanded descriptions. Descriptive essays take describing to a new level. When writers explain the differences and similarities between two topics or ideas, this is descriptive writing with an expository punch! Here, the writer gives a complete explanation of the topic at hand, providing evidence, examples, and even background history. This because, the ultimate goal is to try out an idea that is set forth via a thesis statement. Expository writing, of course, has a clear purpose: to educate the reader. As example, students will embark during the first week on a journey that will enable them to Write an Orange. In order to develop a thesis they will explore the concept of orange, explore some science of the color and the fruit, they will even consider a famous quote by Vincent Van Gogh: “There is no blue without yellow and without orange.”

Over the course of five lessons, again designed to be completed in ten weeks but easily adapted to longer, students will journey with Volume 2 into the work of bringing shape to an original idea conveyed in the form of an expository description, a descriptive essay.

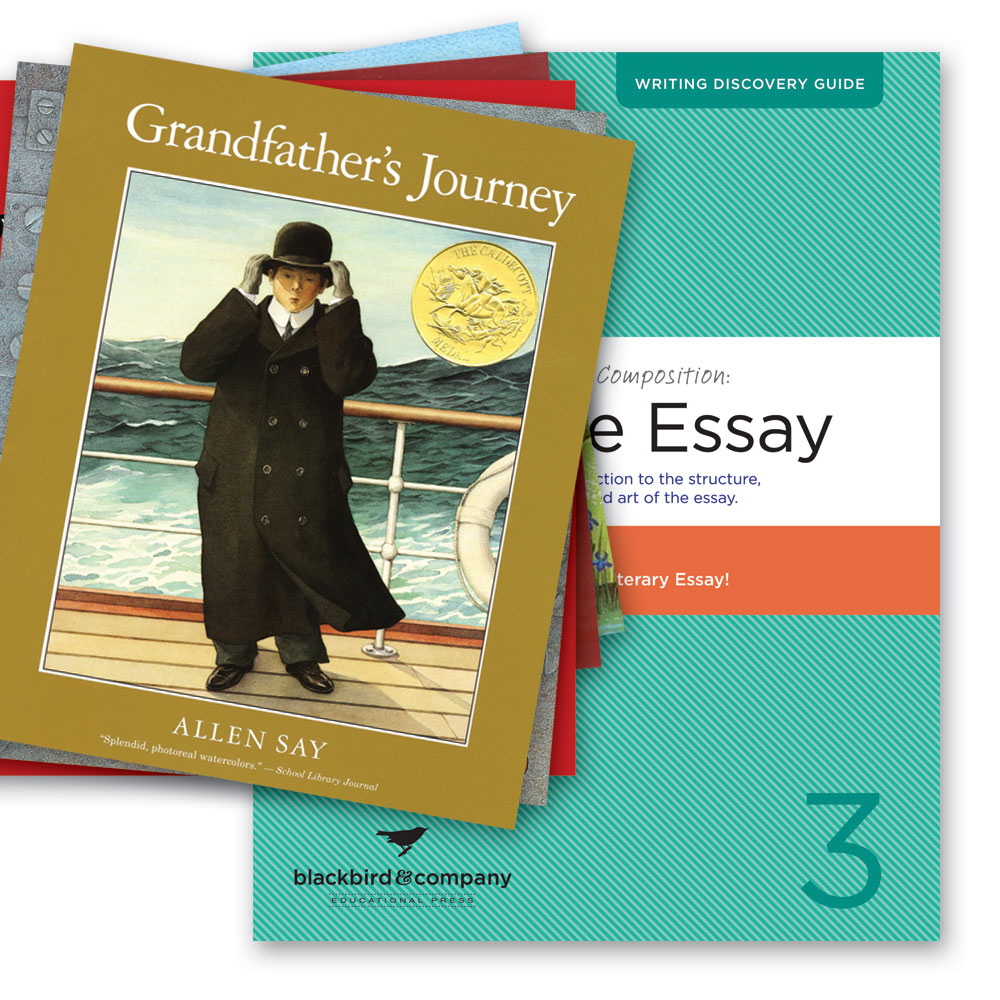

Volume 3 – The Literary Essay

Students are mentored through each step of the process as they compose five original literary essays in response to five exceptional small tales—beginning with a prompt, brainstorming, crafting a thesis and developing the idea through the self-edit and final draft. The literary essay is, of course, expository in nature because the writer will be exploring topics encountered in great stories to provide information gathered from a close reading. While the student essayist will decide which information—character development, themes, symbols and so on—is to be presented, the information is presented not as opinion, but as wonderful factual information gleaned from fiction that applies to the non-fictional realm. The student essayist will explore the literary work from various angle, providing information in an objectively creative manner.

Introductory essays will spring from the following stories:

- The Tin Forest, by Helen Ward

- Grandfather’s Journey, by Allen Say

- The Story of Ferdinand, by Munro Leaf

- Train to Somewhere, by Eve Bunting

- Letting swift River Go, by Jane Yolen

Let me leave you with an important quote from E.B. White:

“If there were something that was less than nothing, then nothing would not be nothing, it would be something – even though it’s just a very little bit of something. But if nothing is nothing, then nothing has nothing that is less than it is. Writing is an act of faith, not a trick of grammar.”

I think what he is saying, more eloquently than I ever will is: Form Follows Function!

Your students will transcend benchmarks as you challenge them to write their ideas!

~Kimberly