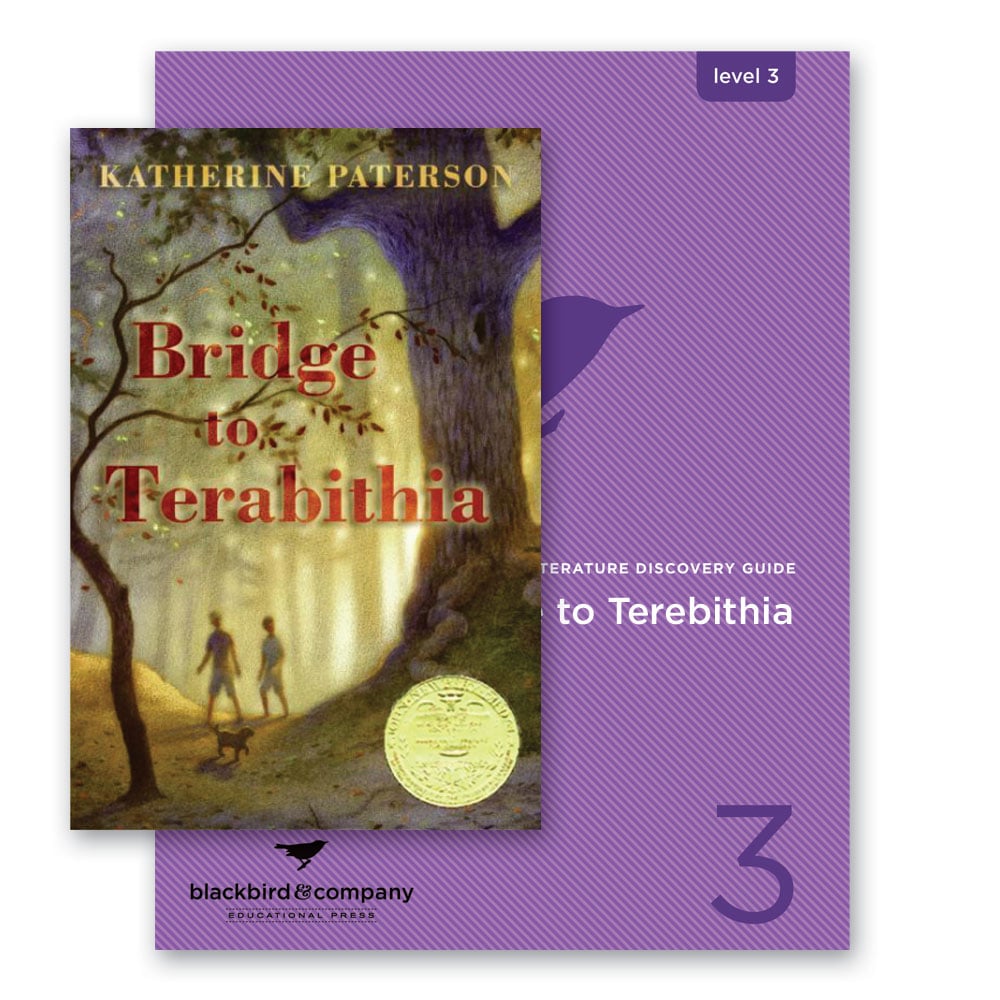

Bridge to Terabithia is a quintessential middle school read. It is tied to one of our CORE, Level 3 Integrated Literature and Writing units. By the time students reach this level, they are confidently journaling and writing their ideas inspired by great stories. As the teacher, you have the profound opportunity to guide your students into the work of unpacking the story. During middle school, introducing the concept of themes and symbols and motifs conversationally adds richness to the discussion and depth to what is gleaned from the story. Following are seven tips for going deeper into this wonderful story.

ONE. Be WOWed!

As you, the teacher are WOWed, your students will follow.

First things first:

Often, we are asked, “Do I have to read the book?”

Our reply? A resounding, “No, you GET to read the book!”

(You won’t be WOWed if you don’t read the book!)

Our CORE Integrated Literature and Writing Journals are designed to free up the teacher to read closely alongside the student, unlocking the story’s treasure. This enables the student to journal observations and compose ideas inspired by the journey.

No skipping pages!

Recently when Cathi and I began to prepare to deliver a close reading lesson of this wonderful novel, I broke the cardinal rule and skipped what I assumed was a “promo” blurb. But no, I realized, upon reading that this significant passage reminds us that someone long ago hung a rope!

“A Place for Us” is actually an invitation to enter into the story’s world, the story’s wonder—”It was a glorious autumn day, and if you looked up while you swung, it gave you the feeling of floating. Jess leaned back and drank the clear rich color of the sky.” Then Leslie called to Jess, “We need a place just for us.” And so the world of the story is opened to us readers.

Thankfully, Cathi reminded me to NOT skip this introduction!

Ask yourself, “What are the powerful points that bring shape to the big picture?”

What are the points YOU discover? What are the points your student discovers? Remember there is no right answer here. There are parameters—think about the characters, the setting, the plot, and all the words and phrases that help these fold together into a story—but within those parameters, there is room to explore.

Jump to the FORWARD written by Kate DiCamillo

“In afternoons the floor would fill up with great slabs of light, and it was very much like being in a dusty, book-filled cathedral. I read Bridge to Terabithia in one of those great squares of light; and the story, for me is forever associated with light.” Reading this brought to mind Emily Dickinson’s poem “A Certain Slant of Light” and the HEFT/weight that the poet describes is akin to Kate DiCamillo’s description here. Robert Frost’s poem, which is also alluded to in The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton is brought to mind too, “Nothing Gold Can Stay.” Kate DiCamillo here makes an astonishing simile: “Bridge to Terabithia is like that room—brimful of light.” She goes on to remind us that something terrible happens. Something terrible. And then she reminds us that we CAN bear this terrible thing. This is the power of literature, it reminds us we are, “…loved and seen, too” (x).

TWO. Seek Out Rich Words

From the Forward…

Rent – to split, to be torn

Brimful – full to the very top edge

“We are devastated, emotionally rent. But still: we feel held, loved, seen. Someone trusted us enough to tell us the truth and because of that the room is golden, brimful of light” (xi).

To the middle of the book and beyond…

Wheedling – To flatter, to coax

“‘Why can’t we charge some things,’ Ellie said in her wheedling voice'” (101).

THREE. Introduce & Explore Themes and Symbols and Motifs

Themes emerge as characters move through the world of the story. Themes connect readers to deeper conflicts that arise on the journey—shared humanity. Themes are NOT “morals” (recommendations on how to live / “moral of the story”) but rather, point to real ways we humans experience the world, archetypical ways. Themes demonstrate topics common to us all—love, conformity, justice, beauty, friendship, courage, power, family and so on.

In other words, it’s NOT a writer’s job to answer the world’s difficult questions, only to SHOW those questions clearly with their stories and allow the characters and the readers to journey through to the other side.

- Cathedral —REVERENCE is a recurring theme that is pointed out by Kate DiCamillo in the Forward. Watch for this throughout the story.

- LIGHT as a symbol is so often repeated in the story that it transforms into a motif, like wallpaper illuminating along the way.

- GOLD When Leslie and Jess help renovate, they want to use blue paint but end up using gold. Ultimately, Leslie compares the room to a magical castle.

- How does FRIENDSHIP unfold?

- How is EMPATHY strengthened?

Significantly, in Chapter 2, entitled Leslie Burke, the character does not introduce herself until the very end: “My name is Leslie Burke” (22). Up until this point, Jess does not know what to make of this person, “The person had jaggedy brown hair cut close to its face and wore one of those blue-undershirtlike tops with faded jeans cut off above the knees. He couldn’t honestly tell whether it was a girl or a boy” (22). After a small dialogue he decides definatively that this is a girl, but is not sure why he makes this decision. So begins a beautiful unfolding of gender as theme, of childhood, of innocence that leads to friendship.

FOUR. Character Development

Characters weave readers into themes.

Look for passages of immediacy where deeper character traits and desires are revealed. In this story, Jess longs to be seen, to be known. He is trying to move beyond the reputation of being the “crazy little kid who draws all the time,” (4) he is trying to win a race, to make his father proud. What was his father like? We know right away he drove a pick-up. But what do we learn about his father that is implied by lines like: ” even his dad would be proud” (5) and “Old Dad would be surprised at how strong he’d gotten in the last couple of years” (6). Later on when the familiar “baripity” can be heard coming up the road, Maybelle screams with delight. When her father opens the truck door, she climbs onto his lap, just then, Jess’s internal voice shares with us readers: “Durn luckey kid” (19). Jess longed for his father’s affection. And teaches us much about his father.

FIVE. Enlist the Built-in Teacher

What is the author doing with words?

Stylistic techniques of the author?

What do YOU discover…?

Comments on Writing Technique

Following are some notes and tabs from Chapter 1 (and beyond). Read these passages aloud and encourage your students to find similar moments in the writing that they find exceptional.

Examine the 4-sentence opening paragraph that begins with onomatopoea. The length of the sentences are short short short and then long. And it is the long, last complex sentence that launches the reader into the complexities of this marvelous story. Read this paragraph aloud!

Check out the simile describing Mama “Mad as Flies” on page 1.

Find this sentence on page 2: “When you were the only boy smashed between four sisters.”

And find this one further on down the same page: “Even if it got unhandy at times.”

This marvelous sentence on page 2 is filled with exceptional words and repetition that lends a certain tiptoe rhythm: “The place was so rattly that it screeched whenever you put your foot down, but Jess had found that if you tiptoed, that it gave only a low moan, and he could usually get outdoors without waking Momma or Ellie or Brenda or Joyce Ann.”

More onomatopoeia on page 5: “…red mud slooching…”

And, in the end, Katherine Patterson profoundly uses onomatopoeia as motif to bookend the story: “Behind him came the baripity of the pick-up but he couldnt turn around” (132).

Watch for the em dash—that wonderful mark that can replace the comma, parenthesis, or colon. This mark is always more emphatic, more intrusive. And Katherine Patterson employs it throughout the story.

SIX. Unpacking the Heart of Story

Pay attention to setting—where and when is the story taking place. This particular story takes place in a small town, Lark Creek, in rural Virginia post Vietnam in the 1970s. Follow the path of the plot, follow the sequence of events driven by the characters. This journey will lead you to the heart of the story.

And as stories go, this one is special—a bildungsroman. Don’t let anyone tell you its a simple “coming of age” story because Bridge to Terabithia is so much more. Bildungsroman is literary term. Here, bildung means “education” and roman means “formation”—loss leads to growth. Here maturity comes at a high cost.

SEVEN. Now Riff to the End

Reading a book is more like listening to music than it is comprehending with right and wrong answers. Reading a book is entering into an art form. And while it is true there are structure and scaffold we can become accustomed to, great stories are unique and lovely and full of wonder.

Eucharisteo is a Greek word that means to give thanks, to be thankful. Reverence. This is the theme that holds this great story together. This reverence begins with the creation of Terabithia. When Leslie names this secret land, “Like God in the Bible, they looked at what they had made and found it was very good” (51). And with that delicious allusion, Katherine Patterson, sets the eucharisteo into motion.

Pay close attention to Miss Edmunds and Maybelle and, ultimately Mrs. Myers who have suprisingly significant, albeit supporting roles to play on the journey through this story.

Remember that the Bridge to Terabithia is a mighty symbol. Keep in mind the idiom “building bridges” is a phrase overflowing with hope.

Then and only then will you be ready for Chapter 10, The Perfect Day, where tension builds and climax swells. Then and only then will you be able to hear Mrs. Myers: “‘Excuse me, she said, ‘this morning when I came in someone had already taken out her desk'” (159). And then this: It—it—we—I never had such a student. In all my years of teaching. I shall always be grateful—” (159).

In that moment Mrs. Myers makes herself vulnerable, sharing her devastation at the loss of her husband. Jess is suddenly in the light, able to empathize, able to replace bitterness toward Mrs. Myers for gratitude. In that moment of tragic illumination, myth-busting occurs. Revelation. Jess is able to understand Mrs. Myers and Mrs. Myers is able to understand Jess.

~Kimberly and Cathi