Writing is an art form.

Writing is an art form achieved via a series of steps:

1) It all begins with an IDEA. Without an idea, the writer will simply stare at the blank page.

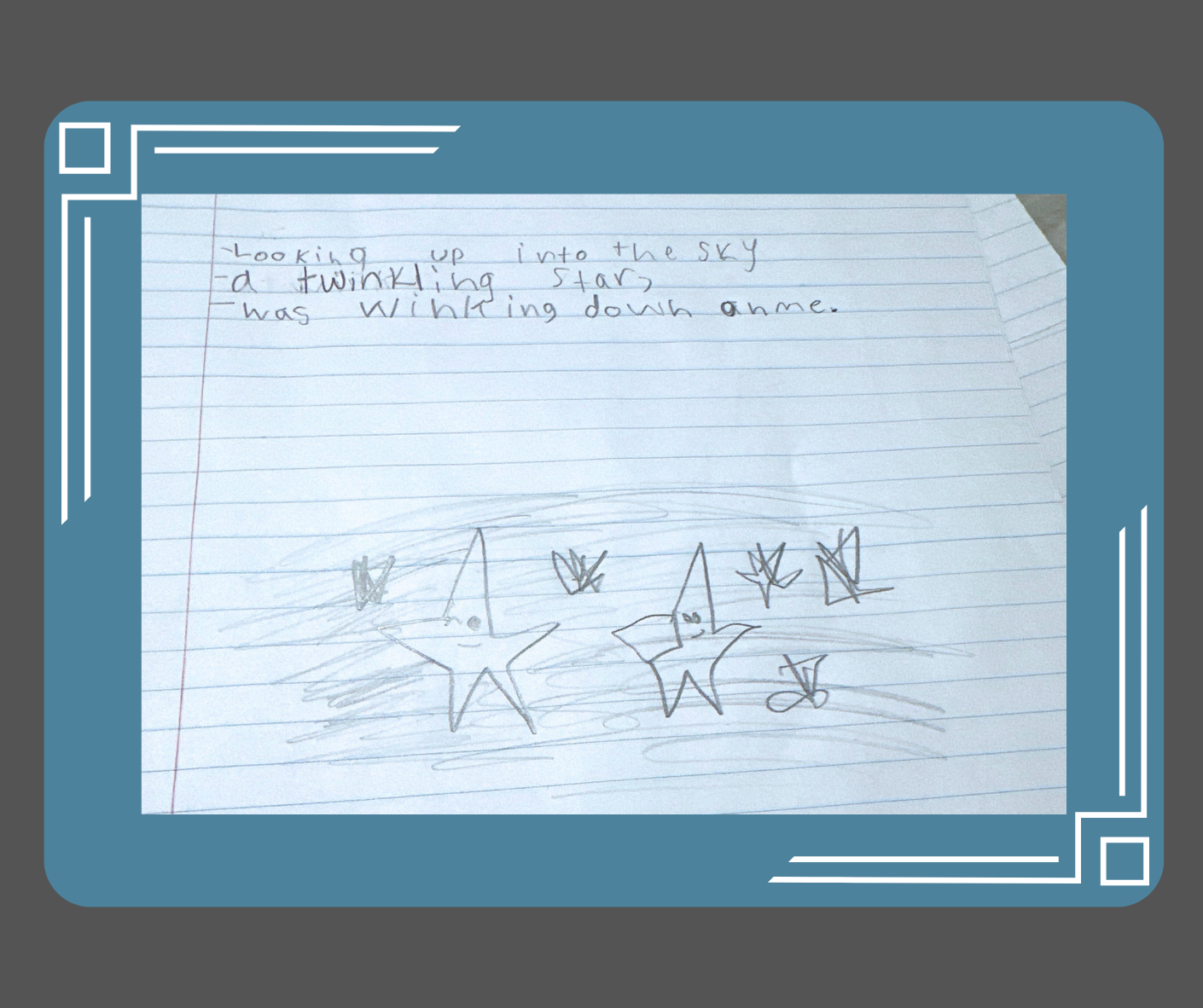

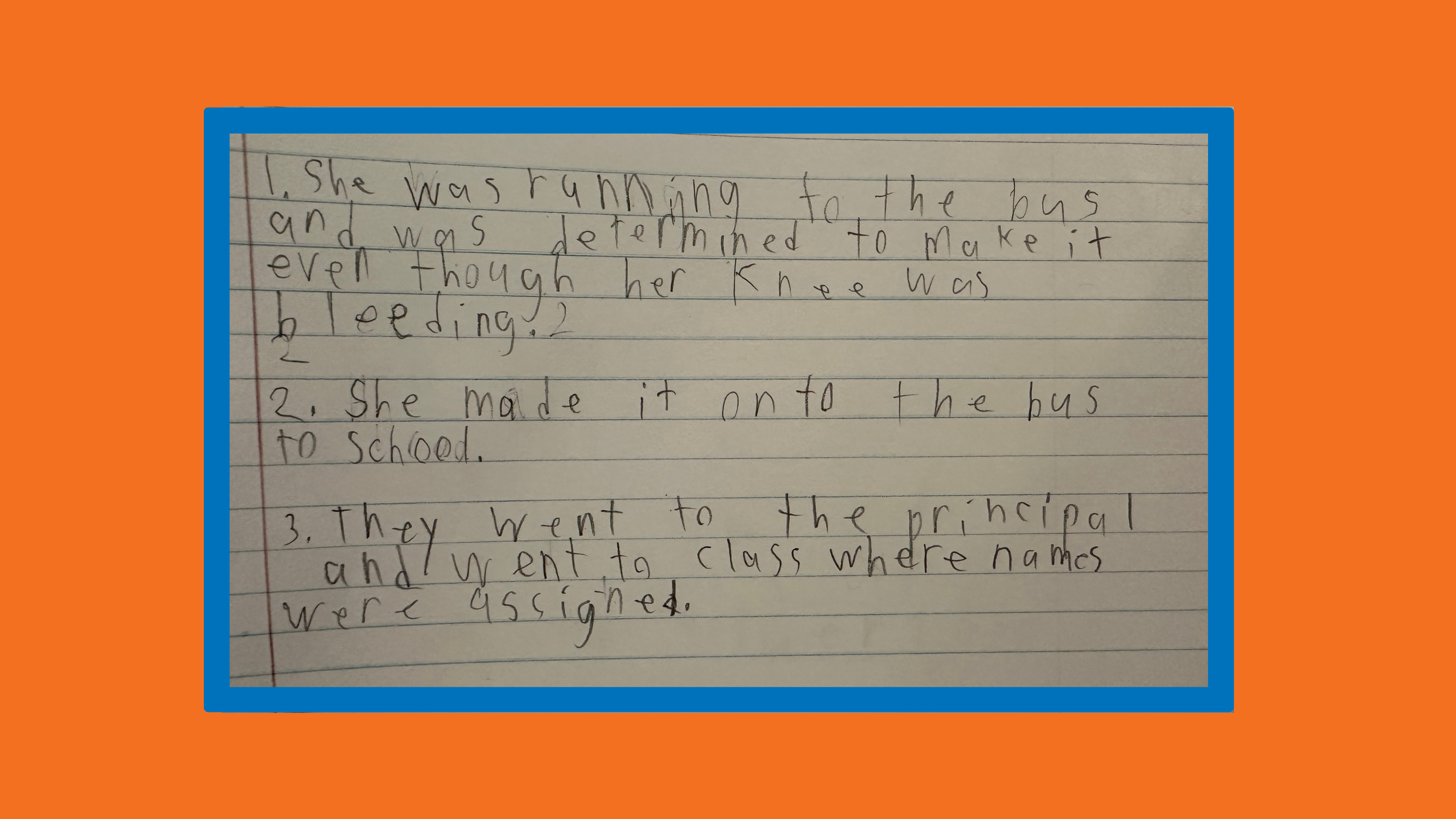

2) Once there is an idea in the mind of the writer, the PENCIL steps in to translate thoughts to words on the page.

3) When the pencil’s work is complete, the job of the writer is to become a READER. Encourage your students to RE-READ everything they write.

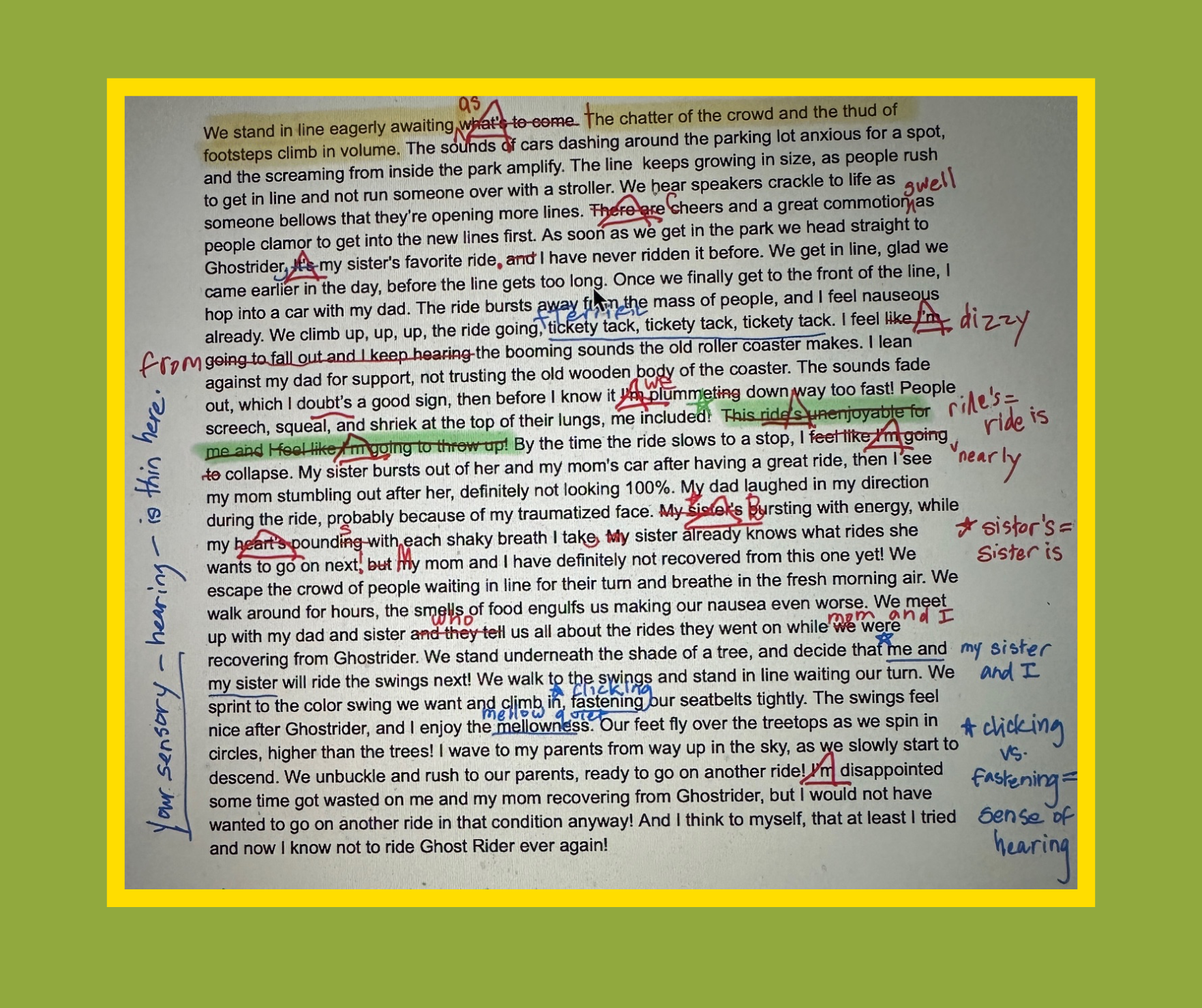

4) Empower students to use the

RED PEN as they re-read to REVISE. Teach them to use strong words, to fearlessly re-arrange, to make corrections, and to not be afraid to strike through.

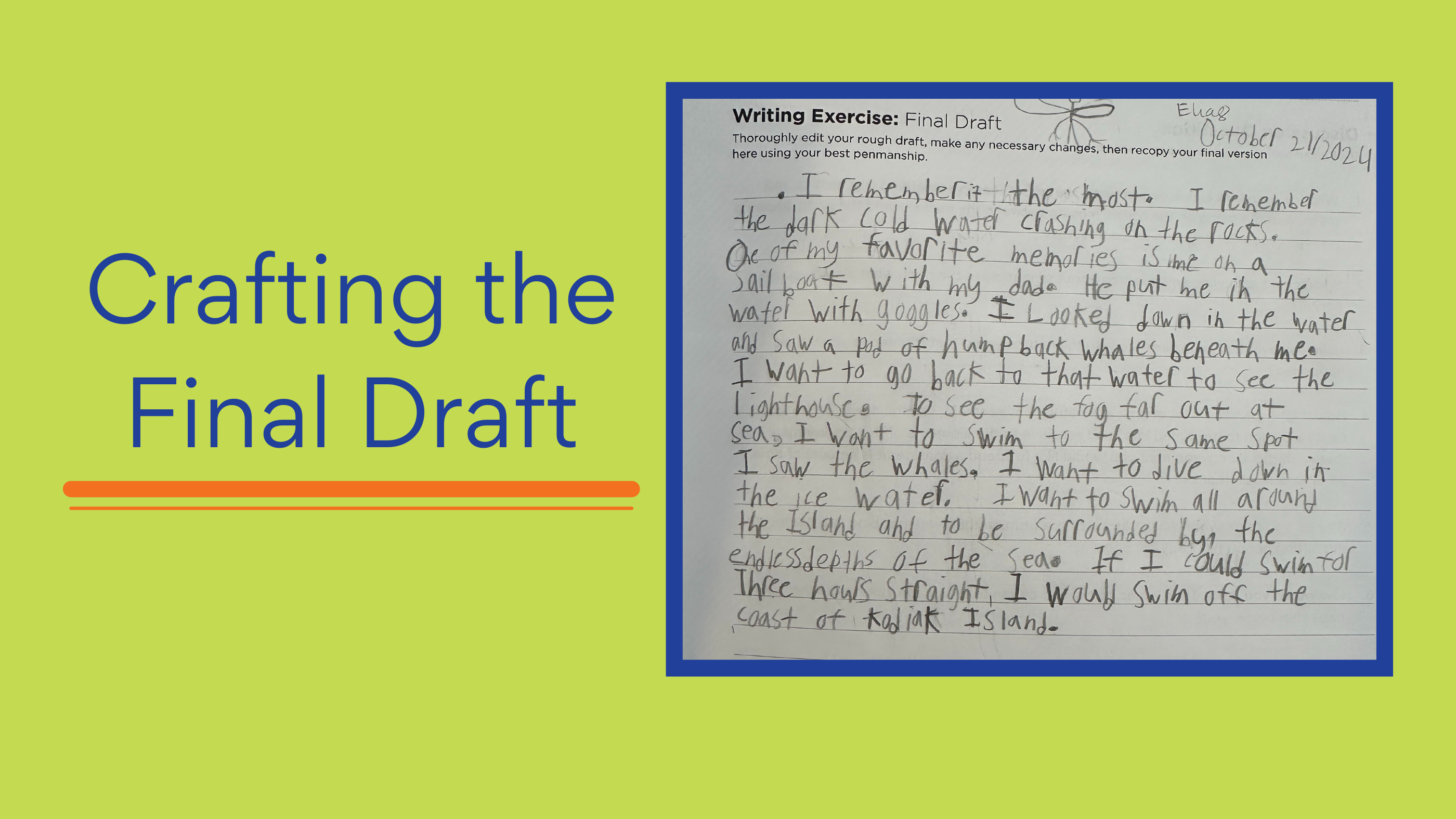

5) Polish the draft, preferably in cursive by hand.

So how does this happen?

THINK Tortoise (not the hare).

Learning to write is a long journey. We know this to be true. And, on this journey, there is NO better technology than the PENCIL.

When it comes to literacy, much of the exceptional work that your students will accomplish is subjective in nature tied to their ideas. As students read great stories, they make observations. These observations will inspire ideas. Cataloging ideas in writing—pencil on paper—over time builds confidence, develops voice, and promotes perseverance.

The PENCIL enables student writers to engage the brain in multisensory ways. When we write we 1) HEAR the idea stirring in our mind; 2) We SEE the letters and words we are forming; and 3) We engage HAND-EYE coordination.

Here are some ideas to inspire PENCIL work:

Mastering the art of handwriting fosters the ability to concentrate, to contemplate, and to communicate confidently. Download our FREE handwriting worksheets here and here. Cursive is not only a beautiful art form, it is a skill that promotes concentration.

Encourage your students to sharpen some pencils!

More than 15 years ago, my mother-in-law enlisted Liam with the task of sharpening fifteen dozen pencils that she would be taking to an orphanage in Uganda. I appreciate how she organized these perfect child-sized humanitarian activities for my children.

Liam got to work immediately. At one minute per pencil, 180 pencils, the task would take about three hours without a break! The task actually took Liam most of the morning. At one point he came in and asked me if he could use the manual pencil sharpener.

“The electric one might be faster.”

“But it’s clogged.”

“Okay Liam, sure.”

“Thanks Mom.”

***

A couple of hours later Liam came bounding into the kitchen with a pencil stained grin holding the sharpened pencils tucked tidily back into their original packaging.

“Wow Liam, all these sharpened pencils!”

“I hope the children in Uganda are happy when they write!”

I choked back the lump in my throat, “I hope so too Liam. Well done son.”

Later that evening I went into the studio to tidy up, and there it was, a brand new installation—our manual pencil sharpener had somehow been removed from its perch in the pantry and re-attached with screws to our antique Craftsman desk! After a moment of letting the shock settle, I let a little smile crackle. My son set up shop, got the job done, and I must admit, to this day I am super proud.

BIG ideas written beautifully by hand with a PENCIL on paper are a gift!

~Kimberly