About a dozen years ago, a friend shared with me that she decided to bypass teaching her children the art of penmanship. Her children would jump straight to keyboarding: “This is the computer age. Cursive handwriting is archaic. Why do the work?”

What about beauty?

When I pressed her, my friend agreed that handwriting is an art form. She simply did not see the value of her young children expending effort to master an art form that would not be useful in college a decade or so in the future. This was my first encounter with creative illiteracy.

Mastering the art of handwriting fosters the ability to concentrate, to contemplate, and to communicate confidently.

Let’s face it. We are a distracted people. We are technology-centric, and our children are at risk. We are obsessed with digital signals that tickle our attention.

But we all, somewhere deep down, appreciate ideas that are beautifully inked by hand. I, for one, long for this personal touch. Of course, there are countless typographical fonts that mimic hand-written text. We download them for free. Sometimes we even pay for these fonts. But can the illusion of written-by-hand really fill the void?

Technology is here to stay. We all need to be technologically literate. I’m connected to my iPhone because I value the many benefits this technology offers.

But what if a technological world without the balance of human artistry is shrinking individuality?

My eldest son is a composer. Until recently, he composed all his pieces by hand on archival paper. When he was a college student, his professor pulled him aside and praised his melodic compositions that are equally beautiful to the eye. However, while he crowned Taylor one of the last “by-hand” composers, he suggested that purchasing a notation program such as Sebelius would be imperative. This is not because the program will make Taylor’s work easier, but because most musicians who will read his work have never played music that is handwritten and the foreign individual nuances are challenging to interpret. Taylor purchased the program, but assured the professor that he will always begin the process of composing by hand hoping to, in the end to also be known for the individuality of his hand on the page.

This got me to thinking, how many times do children come to me and say, “I can’t read cursive.”

Handwriting is an extension of the writer’s voice. Lettering by hand—whether it’s verbal or musical—is beauty, is unique voice. C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien encouraged one another as writers, still, their voices on the page are vastly different. Voice is the fingerprint of the writer, that one-of-a-kind something that no two writers have in common. Our handwriting is a beautiful extension of that voice. We are known by the whisper of our loops on the page.

Remember, “All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence you know.” That’s Hemingway, of course, from A Moveable Feast. I want to add: Ink your one-true-sentence by hand onto paper in the most beautiful way you can!

Try carving out fifteen minutes a day to compose one true sentence, but not just the truest sentence you know, the truest-most-beautifully-handwritten sentence you know!

Begin with these things in mind:

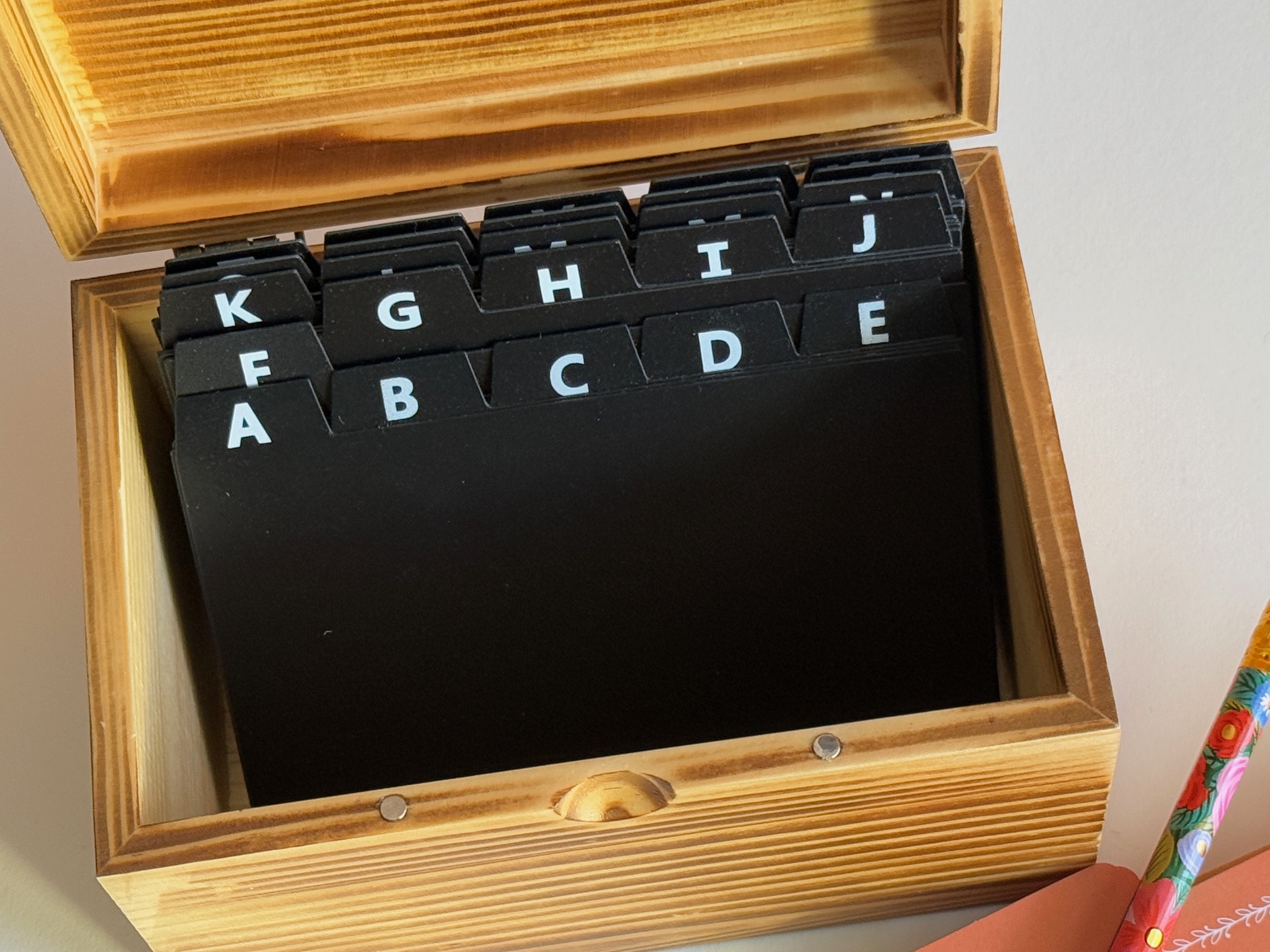

Choose the right writing implement and the right

paper. The feel of the pencil or pen on the page is a personal choice. The balance of resistance and flow has to be just right. Take time to explore the options.

Consider grip and posture. While I don’t believe there is a single right way to grip the writing implement, I do believe the pressure of the grip matters. The grip should always be relaxed, not cramped. The posture should be upright, comfortable, and the arm should rest on a table so that the arm directs the stroke, not the wrist.

Beautiful handwriting begins with beautiful lines. Remember, our alphabet is a set of symbols developed by human beings to represent spoken sound. The symbols, from an artist’s standpoint, are arbitrarily looped and curved lines that

represent the spoken word. There are many letter forms in the world. You might even add one of your own!

Be the tortoise. Slow handwriting is nimble. Slow and steady is non-chaotic. Fast handwriting is mindless, awkward. Fast and rickety is chaotic. Consider the metaphor. An investment of time practicing the art of handwriting will generate much more than beautiful strokes on the page.

Click through to access our FREE lettering by hand activity to get the tradition started.

~Kimberly